Today it was announced that the BBC’s New Media operations are going to be restructured radically. At the moment most of the content creation parts of the organisation are kind of co-owned – for example, Simon Nelson who was the ‘controller’ of the part of the BBC that I used to work for (BBC Radio and Music) reported equally to Jenny Abramsky (in charge of the BBC’s radio and music operations) and to Ashley Highfield (in charge of the BBC’s New Media Operations). Ashley himself had pretty much direct control over a centralised part of the organisation known internally as New Media Central.

After working at the BBC for a few years, it seems to me that this structure was a sort of clumsy compromise that had a lot of problems but a lot of benefits. I wasn’t in the right positions to see the whole picture but there seemed to be organisational and communication problems with such a layout, and a certain splitting of resources. But on the other hand – and this is a big other hand – increasingly the divisions between ‘new media’ stuff and content creation were able to blur, creating new opportunities for each to support the other which couldn’t help but be a good thing.

The other thing which almost seemed to me to be a good thing – sort of by accident – was that it created an environment where parallel parts of the BBC could operate independently and in a rather more agile fashion. More specifically still, it meant that certain parts of the organisation with a kind of critical mass of smart and clued-up people could really thrive and generate their own culture and goals and get things done, even as others weren’t doing so well. It may be just because I worked there or Stockholm syndrome but I rather think that BBC Radio and Music was one of those places, and despite the fact that a bunch of my favourite people have since moved on, I think it probably still is.

Having said that not all parts of the organisation were similarly dynamic, despite the often amazing number of talented people working within them – specifically, in my opinion, Central New Media under the direct management of Ashley Highfield.

You’ll have heard a lot of announcements coming out from his part of the organisation over the last few years, but surprisingly few of them have amounted to much. They all made headlines at the time, but they’ve all rather disappeared. Do you know what happened to the grand plans of the Creative Archive or the iMP? They were both being talked about in press releases in 2003, but the status of the iMP now appears to be a closed content trial and the Creative Archive has amounted to nothing more than a truncated Creative Commons license used by several orders of magnitude less people and a few hunded short clips of BBC programmes. Highfield’s most recent speeches from May this year are still talking about these projects, with him showing mock-ups of potential prototypes for the iMP replacement the ‘iPlayer’ that could be the result of a collaboration with Microsoft. Are you impressed by this progress? I’m not.

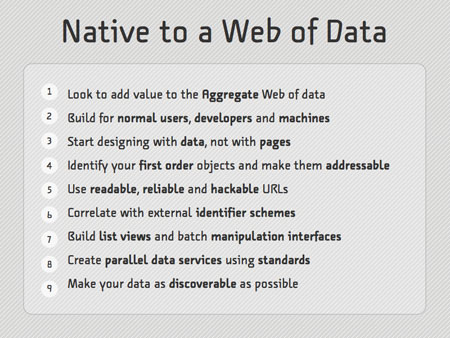

And then there’s BBC Backstage – a noble attempt to get BBC APIs and feeds out in public. What state is that in a couple of years down the line? Look at it pretty closely – despite all the talk at conferences around the world – and it still amounts to little more than a clumsy mailing list and a few RSS feeds – themselves mainly coming from BBC News and BBC Sport. There’s nothing here that’s even vaguely persuasive compared to Yahoo!, Amazon or Google. Flickr – a company that I don’t think got into double figures of staff before acquisition – has more public APIs than the BBC, who have roughly five thousand times as many staff! This is what – two years after its inception? Even the BBC Programme Catalogue that came out of this part of the organisation a while back has gone into a review phase (do a search to see the message) without any committment or indication when it’s going to be fully opened up.

I’m sure – in fact I know – that there are regulatory frameworks that get in the way of the BBC getting this stuff out in public, but these long lacunae go apparently unnoticed and unremarked – there’s an initial announcement that makes the press and then no follow-up. If Ashley Highfield really is leading one of the most powerful and forward-thinking organisations in new media in the UK, then where are all these infrastructural products and strategy initiatives today? And if these products are caught up in process, then where are the products and platfoms from the years previous that should be finally maturing? It’s difficult to see anything of significance emerging from the part of the organisation directly under Highfield’s control. It’s all words!

And that’s just the past. This is a man who decides to embrace social software and the wisdom of crowds in 2006 – clearly waiting for Rupert Murdoch to buy MySpace and show the self-appointed R&D lab of the UK new media industry the way. His joy for this space is expressed in lines like, “The ‘Share’ philosophy is at the heart of bbc.co.uk 2.0 … your own thoughts, your own blogs and your own home videos. It allows you to create your own space and to build bbc.co.uk around you”, which is ironic given that earlier last year he stated in Ariel that he didn’t read any weblogs because he wasn’t interested in the opinions of self-opinionated blowhards. This is a man who apparently coined the term, Martini Media and thinks that expressing your future strategy through smug references to 1970s Leonard Rossiter-based adverts is a surefire way to move the ecology forward. This is a man described by the Guardian in its Media 100 for 2006 as follows:

Exactly how much the impetus for such initiatives stem from Highfield, and how much from the director general, was the source of some debate among the panel.

“Ashley Highfield is among the most important technology executives working in the UK today,” said one panellist. “Yes, but talk about being in the right place at the right time,” said another. “Mark Thompson should be credited with the vision, not him.”

This is a man – bluntly – whose only contact with Web 2.0 that I can find is a pretty humiliating set of pictures on Flickr of him on a private jet and ogling at half-naked dancing girls. (Note: This set of pictures has now been taken down).

So it is, I’m afraid, with a bit of a heavy heart that I can report that the restructuring of the BBC is going to result in a much larger role for Ashley Highfield within the organisation – managing (according to the Guardian, and I’d take this with a pinch of salt) up to 4,000 people throughout the organisation. All the new media functions that have currently been distributed will now it seems be directly under his auspices, and presumably more under his influence than those of the programme makers and pockets of brilliant people around the organisation. I don’t know enough about the nature of the restructuring to know whether it’s a good or a bad thing at a more general level, but it’s pretty bloody clear to me that it’s an ominous move.

Which is what makes me so surprised when people outside the organisation talk about how scared they are of the huge moves that the BBC can make on the internet, because the truth is that for the most part – with a bunch of limited exceptions – these changes just don’t seem to be really happening. The industry should be more furious about the lack of progress at the organisation than the speed of it, because in the meantime their actual competitors – the people that the BBC seems to think it’s a peer with but which it couldn’t catch-up with without moving all of its budget into New Media stuff and going properly international – get larger and faster and more vigorous and more exciting. I want the BBC to succeed. I want it to get stronger – I think it’s a valuable organisation to have in the world and I think it sits perfectly well alongside the mix of start-ups and corporates that’s emerging on the internet. And it’s for precisely this reason that I’m concerned about these moves.

Who’s afraid of Ashley Highfield? I am, and you should be too.