This is a transcript of a talk I gave at Webstock in New Zealand in February 2016, lightly edited to remove many terrible jokes. For more information about Webstock, New Zealand, the artwork in this piece and more more, skip to the bottom of the page to the unnecessarily long transcript. It’s also a repost of an article I posted to Medium. See the talk in its original context.

What I’m going to be doing today:

Today I’m going to be talking about the thinking we’ve been doing at Thington about the right and wrong ways to interact with a world of connected objects, and some of the problems we’ve been trying to solve.

In particular I want to talk about the relationship we’re starting to build between physical network-connected objects and some kind of software or service layer that sits alongside them, normally interacted with via a mobile phone.

And I’m going to talk a bit about how there’s a push in the design community to find a different model, dissolving the top layer here into the object itself through (a) tangible, physical computing, or through (b) metaphors of enchantment or magic:

I’m going to try and argue that both of these models are kind of wrong! And I’m going to be chatting about a few ways that I think we could and should be a bit nicer to the software or service layer (with a nice long digression about tangible computing on the way).

This is, by all accounts, a pretty deep, weird and nerdy talk, through which I hope to expose to you some of the insane depths of computer history and the weird arguments designers have.

But first a little history…

A brief history of computing in the Twentieth Century:

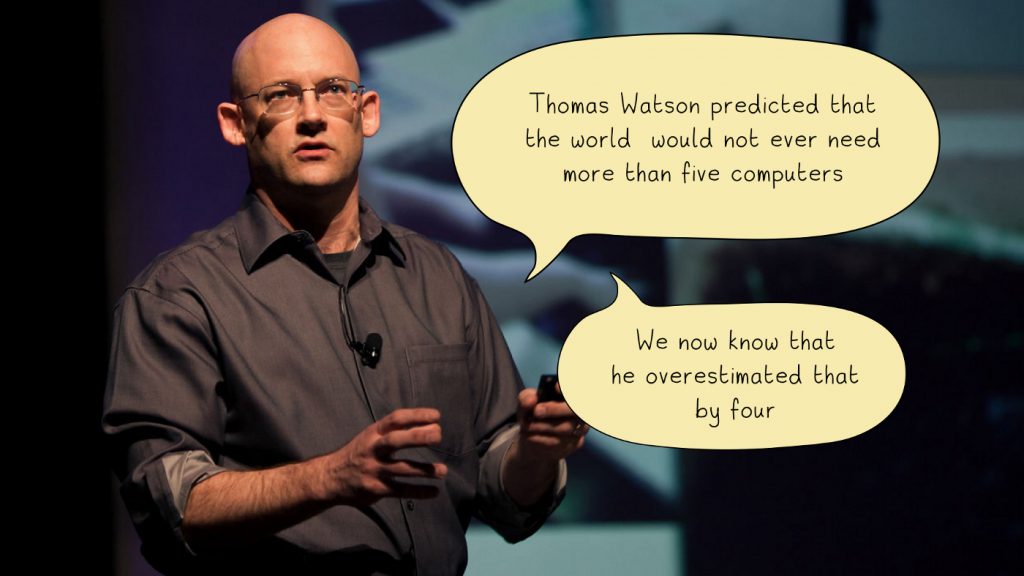

We’re going to start with Thomas Watson — the gentleman founder of IBM — and a statement that he is alleged to have made in 1943 that sounds crazy and entertaining to modern ears. That statement is:

There’s actually very little evidence he made this statement at all, but at the time it wasn’t a particularly unusual statement to make. For example, Charles Darwin’s grandson — who was slightly unfortunately also called Charles Darwin — said in 1946 of the UK:

And then there’s this chap, early computer pioneer and telepathic supervillain Howard Aiken, who said:

People genuinely didn’t think there were going to be many computers in the world! Even after twenty years — maybe because of twenty years — in the tech industry I find this a super weird thought. I find this a really hard idea to get my head around.

So how did this match up with the actual reality? This following picture is me in the late seventies in my favorite Disney Winnie the Pooh t-shirt, in Norwich in the UK, not looking very cool. This is about thirty-five years after Thomas Watson from IBM’s statement, coincidentally roughly halfway between that statement and today:

In terms of computing, where are we? From the four or five computers that Thomas Watson thought we’d have, we’re already up to the massive 50,000 units of computers sold each year. That’s quite a shift!

Skipping forward another fifteen years or so, here I am again:

Here I’ve finished primary and secondary school, and I’ve gone to University and I’m starting grad school and I’ve popped over to the US to have my photo taken on top of the Empire State Building with my tongue out. At this point in the world there are in active use something like 150 million computers.

Here are pictures of me in the early 2000s (one billion computers have ever been sold) and the mid-2000s (two billion computers have ever been sold).

And then of course this happened:

I think we all forget how quickly things can change, but I think it’s fair to say that the era of the modern smart-phone starts with the iPhone, and it’s really important to remember that only launched a little under nine years ago. This by the way, is the very first advert for the iPhone which essentially replaced single use telephones with general purpose computers connected to the phone network.

Three years after the iPhone launched — so about six years ago now — in addition to all of the desktop and laptop computers we were buying, we were also buying 150 million smart phones a year.

Five years later — 2016 — and it’s projected that 1.6 billion smartphones will be sold. In one single year, one smart phone will be bought for every five people on the planet.

But what happens next? A world of connected objects.

Now the reason I’ve taken you through this little adventure is to just remind you that within a human lifetime, we’ve gone from essentially zero computers sold per year to billions. It’s been a period of an extraordinary increase in the availability of computation — with processors shrinking and becoming more powerful every day. And not only has it been growing at an extraordinary rate, that rate itself is accelerating. The last decade has seen a massive expanse in available computation and it shows no sign of slowing down. We can expect a world of hundreds of billions — trillions — of computers distributed around the world around us within a few years — embedded absolutely everywhere they can make even the slightest incremental improvement.

I’m talking of course about the Internet of Things, and this is where I make my first grandiose assertion of the day:

It’s a time of tremendous change. After years of design experiments and academic discussion, the cost and availability of components and the ready availability of smart phone interfaces means that the Internet of Things is finally rapidly approaching.

In fact, I’ll go further and say that within a decade almost all new electrical appliances and devices that we buy for the home will have some kind of network component — to say nothing of our offices or public spaces. Quite seriously, the world of tomorrow is dripping in objects that belch out information or can take commands, or both…

But don’t take my word for it. This is Samsung’s CEO at last year’s Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, where he made the Internet of Things their major focus:

By the way, CES is an amazing event too. After years of it being something that internet people didn’t really attend, it feels like that’s finally changing as software and computation starts moving into devices.

When I went last year, there were smart dishwashers, heaters, smart air conditioning units and humidifiers, smart lighting, smart garage door openers, things to open curtains, check if your house was on fire, smart ovens and kitchen scales, smart vacuum cleaners and smart security systems. If it could take a battery or plug into the mains there was a smart version of it… And they were being made by companies like Samsung, Polaroid, Canon, Panasonic, Quirky, Sony, Belkin, Parrot, Honeywell and many others.

But how do people access the power of these devices?

Honestly, however good the hardware was at CES and however much of it there was, often the the benefits that thetechnology seemed to bring people just did not seem to be as good as I might have hoped. The power of the internet was just not present in these devices — the networked parts of the product were effectively little more than app-based remote controls.

To me, it was still clear that they were going to be able to offer tremendous power to us all to control and understand the world around us, but there was little sense of how a normal person might harness or grab that power in comprehensible ways.

Now some of you might be even more suspicious and say that there’s little or no power to be discovered in a world of connected devices. I think that’s wrong, but I also think it’s an understandable statement. Some of these devices have been crazy and lurid and wasteful in their use of technology and bring no obvious benefits to their users.

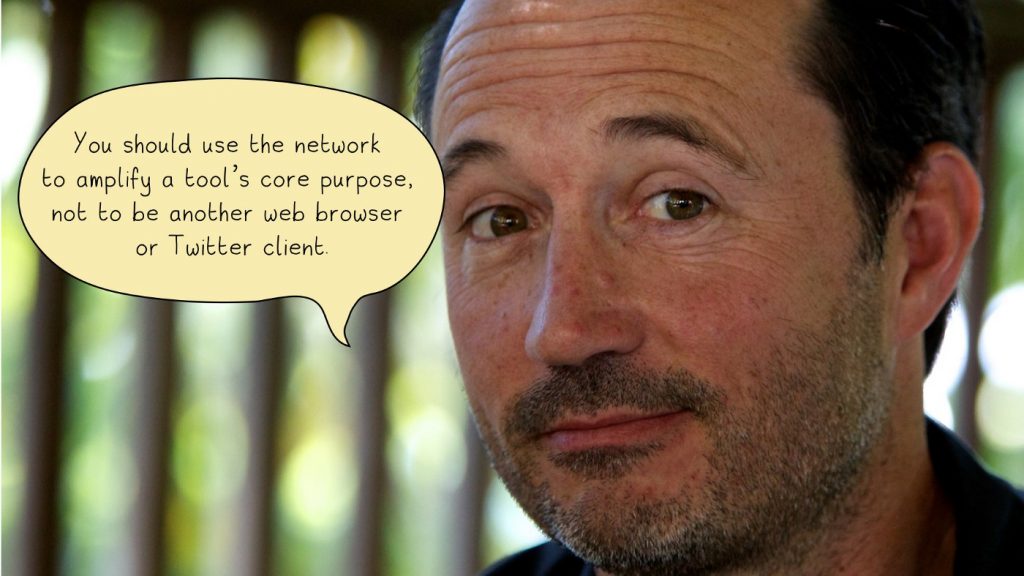

But today, I’m going to focus on those devices that (when enhanced with the internet) get better. This statement from my friend Matt Rolandson from Ammunition Group in San Francisco sums up this category for me:

I really think this is one of the most bluntly useful and apparently obvious things that anyone has said about the Internet of Things as it manifests in devices and appliances. The Internet can and should be used to amplify a devices core purpose and if it does so, it makes that device better and more useful.

But surely there are better ways for us to amplify the purpose of things than just giving them a remote control?

Merging the physical and the digital

Okay — so this is the pattern that I mentioned earlier — essentially there’s an object — here an oven — and it comes with an app that runs on a mobile phone. The app is essentially a remote control for the main object, one that potentially has a few rule making components with it that make it a little more interesting and useful.

This is a model that actually enhances the object it’s attached to — it makes it easier to control or check up upon from a distance, but it seems a bit simplistic and on the nose. Can this really be the extent of the future we’re looking for? And is the reason it feels a bit dull an interaction problem?

One direction that designers have traditionally been very keen to explore is dissolving those two parts together — merging the service layer and physical objects to make something seamless and more powerful, that a user might interact with in both the ‘data’ environment and the ‘physical’ environment at the same time. Essentially the goal here is to break down the distinction between the two parts of the ‘thing’ (actual vs virtual) to make something new and hybridised.

There are so many people making these arguments in the (perhaps more cerebral) parts of the design community that it sometimes seems inevitable that this is the direction that we should be moving in. Let me give you some examples:

This is a quote from Josh Clark (from Connected // Disconnected), who has been talking around IoT on the design side for a while now and is a very sharp guy:

“The potential of the internet of things is to improve on what mobile does so well. Instead of availability at the point of inspiration, IoT lets us shift to interaction with the point of inspiration. Add sensors and smarts to an object or place, and you no longer have to pull out your phone for a digital interaction.”

And this is a quote from Matt Webb in the UK from a piece called ‘Waving, Not Designing’ that he wrote a few years back:

Why use just your fingers to select what’s on a display when you can use your whole body? It’s often easier, and makes more sense. Like, when you use a hammer, you don’t key into system to say “hit at point X with force F” and then stand back and let it happen, you just pick up the hammer and hit with it, using your body to judge strength and your eyes to judge position.

I could genuinely list a hundred other people making this argument. And they’re some of my favourite people in the design community too — people who are looking around, reaching for something truly new and interesting and more intuitive.

This is literally a screenshot from an argument I had on Twitter with a super sharp friend of mine, who is clearly pining for something a bit beyond the model of “phone + thing”.

Designers are looking for a new natural vocabulary for the next generation of devices, and they’re looking towards embodied interactions and tangible computing.

A brief guide to Tangible Computing

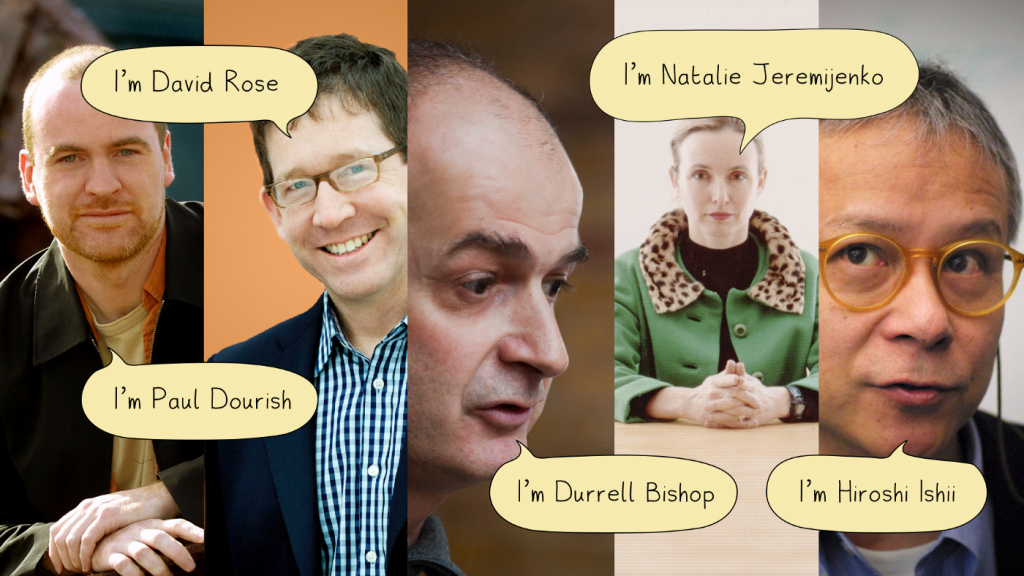

Much of this thinking is inspired by the ground-breaking work of people like Paul Dourish, David Rose, Durrell Bishop, Natalie Jeremijenko and Hiroshii Ishii.

Now I have to apologise here because for brevity I’m going to have to wildly over-simplify their positions (you should go and read and research their work online at least — it’s great stuff) but essentially they want to blur and even dissolve the distinction between the digital and the physical. They think rather than have a differentiated service layer, the magical intelligence should merge with the physical object. And that, in the doing of this, they believe simpler, clearer, more powerful, magical objects emerge.

Their argument is fundamentally that the world of screens and icons is too abstracted and separate from the world around us and the ways in which human beings understand that world.

Let me give you an example — David Rose in his book “Enchanted Objects” talks about four visions of the future. The most awful one he describes is called, “Terminal World”.

“It is years into the future. All the wonderful everyday objects we once treasured have disappeared, gobbled up by an unstoppable interface: a slim slab of black glass. Books, calculators, clocks, compasses, maps, musical instruments, pencils and paintbrushes, all are gone. The artifacts, tools, toys and appliances we love and rely on today have converged into this slice of shiny glass, its face filled with tiny, inscrutable icons that now define and control our lives…”

Now unsurprisingly, David doesn’t want this world to happen (or for phones to eat his children) so he presents an alternative view that he called “Enchanted Objects”. He describes it as ‘technology that atomizes, combining with the objects that make up the very fabric of daily living’ and the examples he provides are really lovely.

One particular example he worked on himself is the Glowcaps system, which beeps and flashes with increasing urgency if you forget to take your pills on any given day. And he talks about many others, including Nest Thermostats that predict your temperature needs, umbrellas with lights upon them that signal up when it’s going to rain that day and many more.

These are genuinely useful and interesting things and there genuinely are more of them every day coming into the world. The Glowcaps alone have a huge impact on people whose drug regimens have to be strictly adhered to.

The metaphor here, as I’ve said, is ‘enchantment’ — magical interactions — bringing the intelligence into the object itself as you would with an ancient sword, rather than believing in the presence of a separate, service layer.

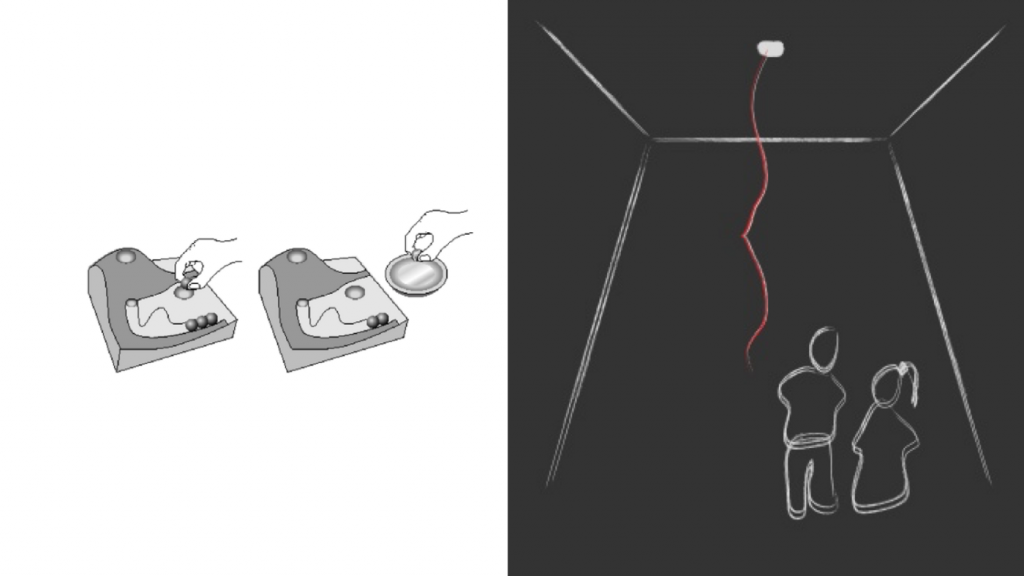

Leaping back in time quite a long way for a moment for illustrative purposes, here are two classic examples from the early nineties of the blurring of the physical and the digital — bringing the virtual representation and the real object so close that they become one definite thing.

On the left we have Durrell Bishop’s answering machine. This pumps out a little marble when you have a message, and you place the marble on a sensor tray to play it back. Natalie Jeremijenko’s dangling string simply indicates the amount of network traffic in a space by twitching a string in a room, giving people an ambient awareness of activity.

I bring these up because they are classics of the field — almost foundations of the field — of tangible computing and were first to articulate some of these goals that we’ve talked about so far..

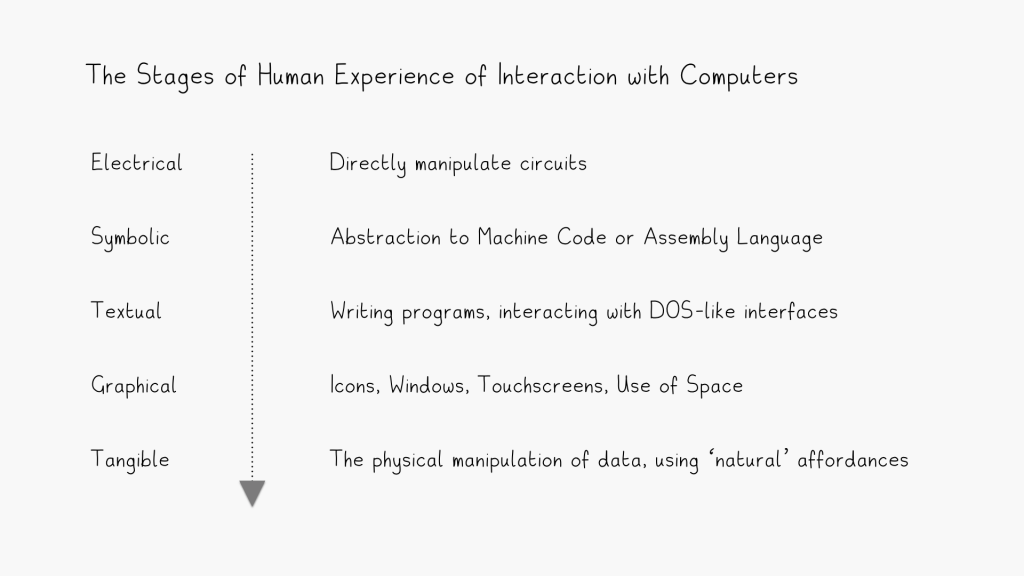

Paul Dourish, in fact, went a step further in his seminal book ‘Where the Action is’ around 2001, suggesting not just that things would be better if the physical and the digital were closer together but that such a path was effectively inevitable and natural.

He framing our interactions with technology as a series of approaches that build one upon the other, each employing a skillset that more closely reflects how human beings understand and instinctively interact with the world.

And it certainly does seem like there continues to be a lot of ways in which more tangible interactions with enchanted objects could provide a lot of power in the world. It’s clear we’ll see a lot more of this kind of approach — the focusing on the invisibility of the technology, dissolving in the use of the object. It promises a certain seamlessness of interaction.

Some problems with merging the virtual and the actual

But is it the ultimate answer to how we interact with a world of connected objects? There’s a desire by people using these guys as inspiration to try and make every object self-explanatory, self-evident, complete and seamless and separate from other things. And that seems like a flawed enterprise to me and it seems to miss where quite a lot of the power of connected objects might be… That is, in the connections.

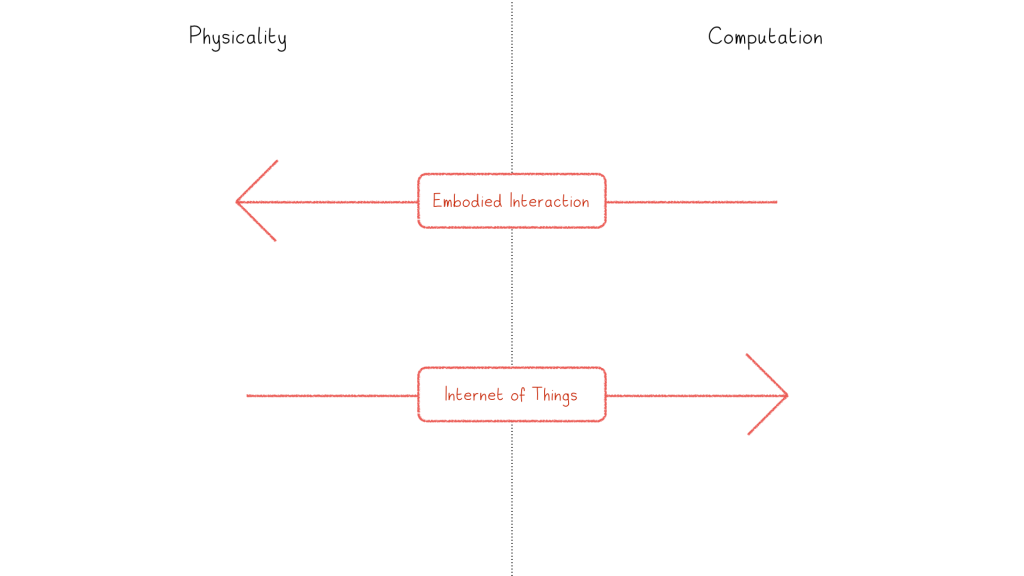

In the first place, I think there’s a bit of a category mistake going on here. For Hiroshi Ishii and Paul Dourish, for example, the work they’re doing is more concerned with using physical interfaces to manipulate data, rather than bringing computation into devices. Their focus seems generally in making the manipulation of digital objects more intuitive by bringing it into the physical, a space that we have dedicated millions of years of evolution to understanding intuitively.

The internet of things, however, is much more about enhancing the physical with the digital, making the objects make more sense at a distance, or drawing out information from them and bringing it into a virtual space where we can do stuff with it.

In some ways, you might argue that the fact that the two merge the physical and the digital is a coincidence — and that in all the ways that count, they are actually opposites of one another.

I’d also add that one of the thing I think contemporary designers miss is that these thinkers were very focused on the environment surrounding the object and the abstract information about who owns it, who can use it, what information the object needs in order to be able to do its job most effectively.

Dourish is very focused on the environment around the things, Rose very focused in the services around the objects. I think it’s a mistake to think that their focus on better objects means less focus on better service layers.

Another example that complicates this tangible vision — in my home, I have various smart lights connected to the Internet but it doesn’t really make sense to me to think of them individually — they’re part of a larger system which is ‘My environment’. What is it specifically that I connect with or touch or interact with to make them act in the world? The objects are definitely acting independently, but it feels like there’s something that connects them.

Again, it feels like something that isn’t situated in the object, it feels like there’s something between them. My intuition is that I’m communicating with or manipulating something beyond the level of an individual object, and it feels like that’s the intuition that in this context we should build interfaces around. Perhaps then the power simply doesn’t come from dragging the network down into the physical thing, but with embracing the network and the object as complementary but separate parts of the same system…

In fact it’s this problem of what’s most intuitive that gives me most pause for tangible computing generally. The assumption from many of these thinkers is that making an interface that’s physical makes it inherently more intuitive.

But I don’t buy that physical affordances alone will make it immediately obvious what a smart connected object is for. Sure, you pick up a hammer and you immediately want to hit something (or maybe that’s just me) — but is that true of a smart hammer?

That seems to me to also be dubious — for every good product that makes more sense when embodied or made tangible, it seems another is likely to pick up some strange magical interaction metaphors that are less intuitive, or even counter intuitive. It’s quite possible that in taking something that is ‘natively’ digital or abstracted and merging it with something else with physical affordances, we create a thing at war with itself. Not more intuitive at all, but just much more confusing.

Are we making things that are effortless, or are we simply creating a whole new vocabulary of interactions that people have to get their heads and hands around?

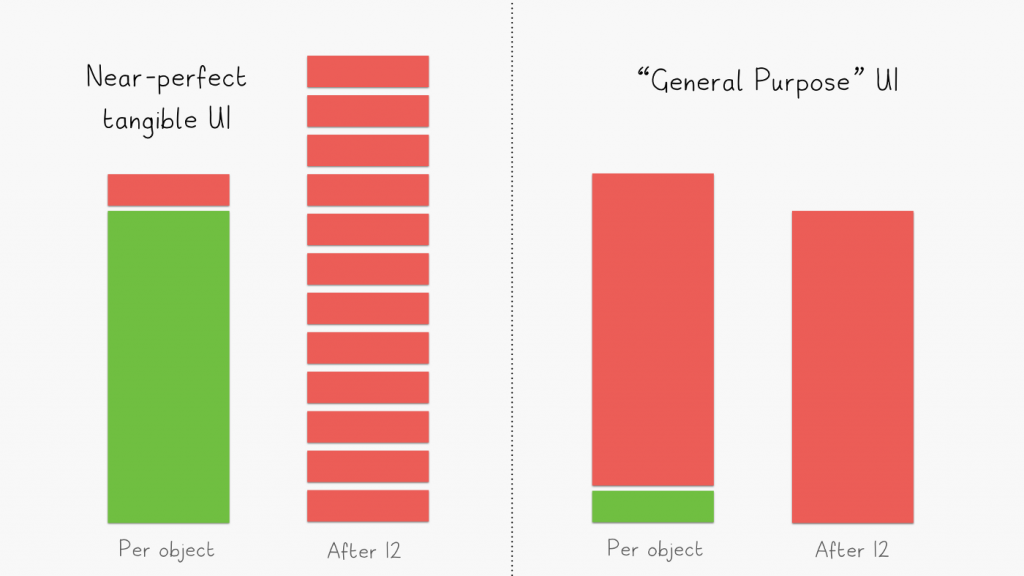

Our cousins in computer engineering talk about General Purpose Computing — whereas as designers we’re often tempted by the quest to find the ultimately specific interface for the thing in front of us. But each slightly different interface creates an extra cognitive load that when multiplied across every object in the world may be wildly less intuitive than a General Purpose Interface on a phone, or smart watch or computer whose abstracted rules we learn once and can then apply everywhere.

In this quick diagram I knocked up, the green stuff is the thing that is immediately intuitive and doesn’t require learning. The red stuff are the bits that you have to learn to use. My argument here is perhaps a slightly harder to learn ‘General Purpose’ UI might have less cognitive load than a whole bunch of nearly intuitive devices where there isn’t any transferable knowledge.

So if the solution isn’t merging the physical and the digital, what is it?

Towards a stronger service layer?

Personally I think the solution of how the physical and the digital should interact is not to bring them closer, but instead try make the relationship between the two clearer and then push the power of the service layer far beyond where it is at the moment. And I think when you actually look at the problems that confront people when they use IOT devices, you end up essentially defining the properties of what that service layer should be.

In a moment I’m going to tell you a bit about what I think that picture looks like, but first — if you’re a designer who is in any way uncomfortable with this idea of the point of interaction and the device being separated from one another — I have a quick example for you from history which might help you relax.

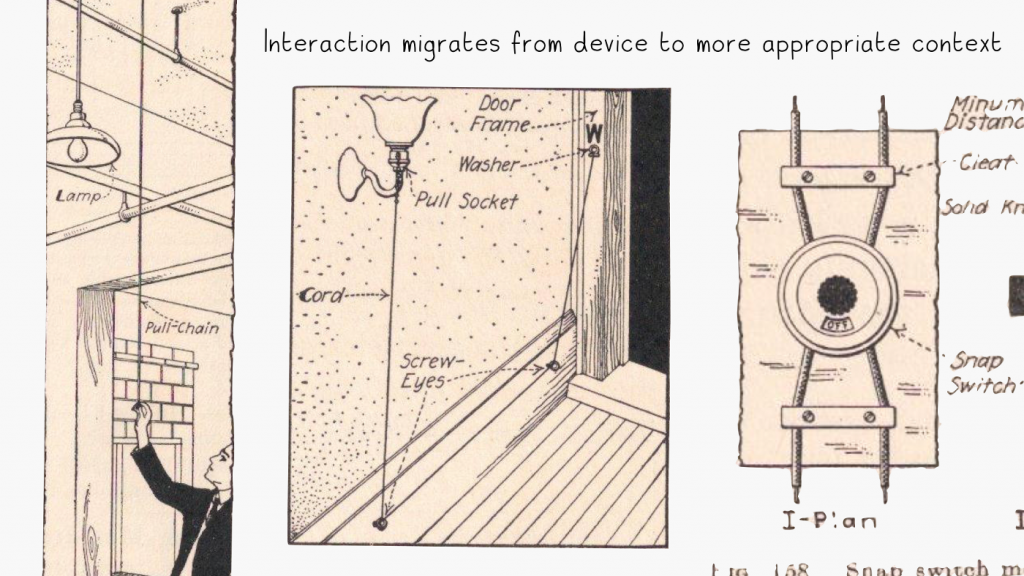

This is the evolution of the light switch. Lighting started with controls directly next to the kerosene, oil or electricity light and gradually moved away from the object itself to the places they made most convenient sense — by the door that you walk in through.

You shouldn’t doubt it took them a while to get there — I love the one with the cord in the middle that uses a sort of pulley system to put the interaction where it makes most sense — but in the end we all decided that we understood that the right place for a light control is just where you want to turn on the light. The light is the thing. The service layer is the switch. And the service layer sits wherever it makes most sense for the person, with the relationship between the two clear and simple.

Here’s a more up-to-date example. Zipcar has cars parked in garages and parking structures across the World. And you can book them online or from the app and open the doors and drive off with them at any time with a simple RFID card.

But the hardware here is trivial — it’s just an RFID reader and a couple of switches, allowing the engine to start and the doors to unlock.

It’s in the service layer that the value of Zipcar truly lies — you probably book the car from home, so you’ll probably book it via your phone. And then you’ll use all those brilliant features of the internet that cars don’t naturally have — an understanding of identity, payment and a sense of location. It’s from that interplay a beautiful and powerful service is born that makes thousands of cars in thousands of locations yours to spin up as a software engineer might spin up an EC2 instance.

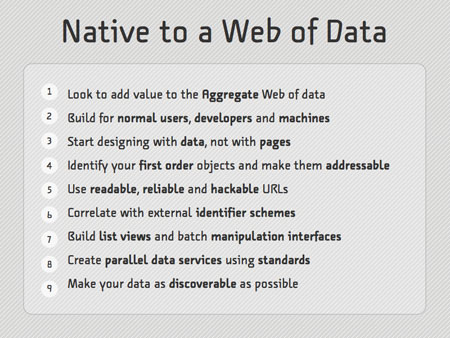

So what is the ideal service layer for the Internet of Things?

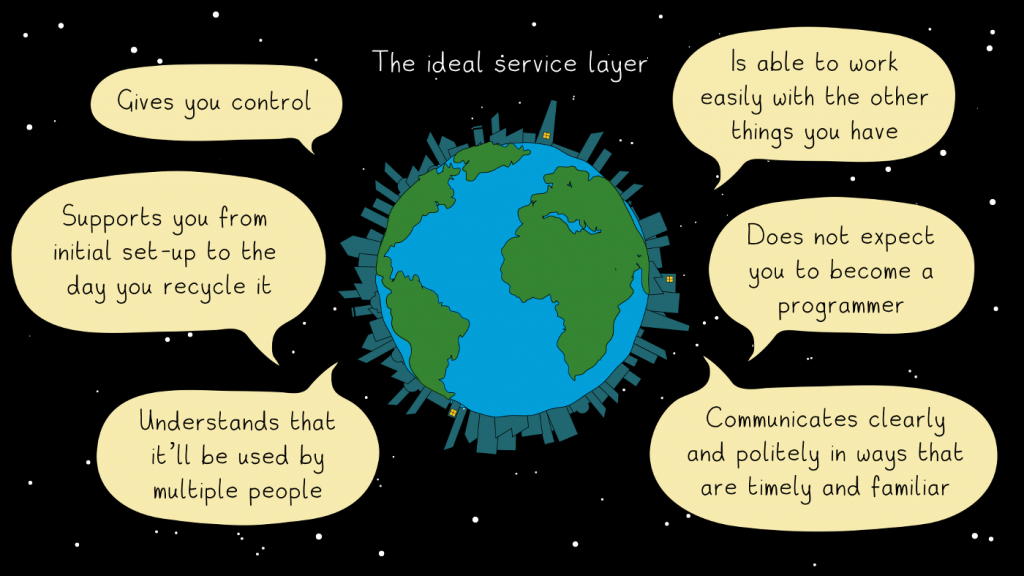

Here are the six things that I currently think are the core features of an enhanced service layer for general smart things.

Number one is nice and simple — the ideal service layer gives you control. It should give you the ability to control an object locally (even though it may be easier to do it through a physical interface) as well as from a distance.’

This is so obvious I’m surprised I have to mention it, except that advocates of embodied interaction always seem to miss that it’s actually a core attribute of a smart device that you don’t need to be physically present to control it or find out information from it. The exciting part of the Internet of Things is the Internet! And the Internet has been about collapsing distance and making the world accessible wherever you are. It’s no different with the Internet of Things.

Number two is about how a service layer lives with you over time. The ideal service layer supports you from initial set-up to the day you decide to recycle it.

This is one of the things I think is most bizarrely missed out on in most IoT products. Owning a piece of hardware is a relationship with a beginning, middle and end. You start off researching something to buy, you choose it, install it, use it, try and set it up to meet your needs, you buy supplies for it, you clean it, occasionally it breaks down and you throw it away, or you get it serviced and fixed. Eventually you decide to upgrade it.

Having a service layer transforms a thing from something a manufacturer sells to something that forms an ongoing relationship between manufacturer and consumer. There’s so much potential there it’s startling.

Number three is a huge one for me and again brings in some of those features that we saw with Zipcar (and interestingly come naturally to light switches). The ideal service layer understands that the device will be used by multiple people.

Again, these are things that if you look at almost other part of the Internet are obvious and baked in. Loads of services build on the Internet have concepts of identity. You can log in as someone and get access to various features. Different people can have different permissions. But for most IOT devices this is still completely absent. (This is a subject I’ve written about before in a piece about Thington: Why people are the most important part of a world of smart things…)

A quick example if you buy a nest thermostat first you install it in your home, then you create an account so that you and the thermostat are karmically connected. Then for every other person who lives in your house, or may come and visit and who you think might have to have some control over the temperature while they’re there, you simply sign in as you on their phones too.

This, I might suggest, is crazy. It makes it effectively impossible for it to react differently to different members of your family! It makes it impossible to know why a room is the temperature it is.

It also makes it possible for someone to come and stay at your house and then once they’ve left your house somehow continue to control the temperature in your house at long distance with you having no way to stop them! This has happened to me and it simply shouldn’t be possible. We should know better. This is easy to fix!

Number four is where all the promise of the Internet of Things lives and yet sometimes feels like the farthest away from coming into reality. The ideal service layer is able to work easily with all the things you have.

A smart light switch is great, but even better if it can coordinate with motion sensors in the house and with the geofences triggered by your phone to turn off precisely when you want them to. A sprinkler system works particularly well if it knows not to turn on when the windows are open, or when it has recently rained, or if you’re just about to walk through the garden.

But even if you have number four, then you still need number five for this power to be even trivially available for people. The ideal service layer does not expect you to become a programmer.

To create the kinds of coordinated responses I just talked about, someone has to somehow encode the expectations and the relationships and string them together. And at the moment there really aren’t any good ways to do this.

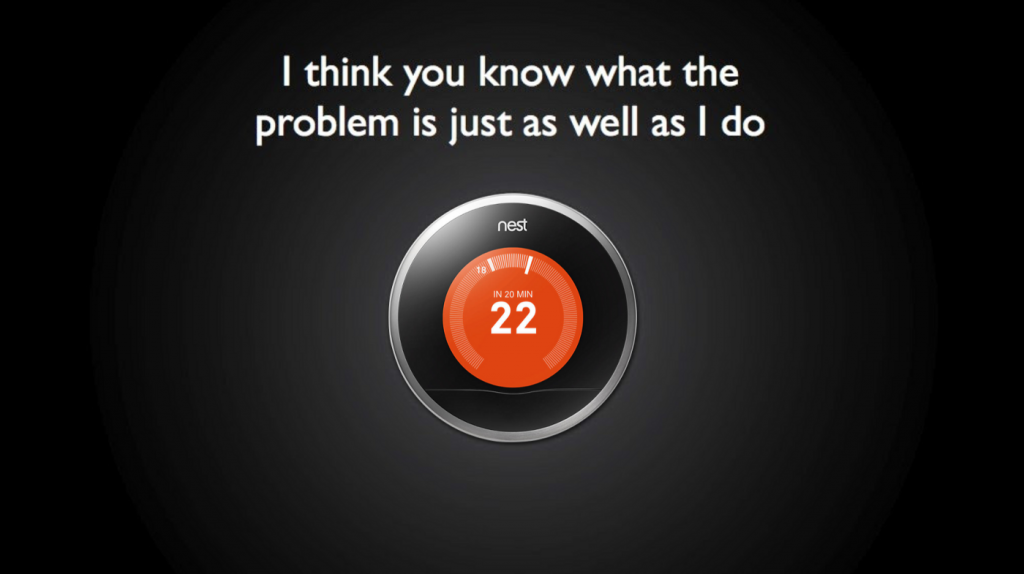

One way to stop you having to become a programmer is to make all the decisions automatically for you. This is the way that Nest attempts to do things — it’s just supposed to observe how you live your life and intuit what you want to do next.

I’ve interviewed dozens of people who have the nest and with a few exceptions they’ve all turned its magical learning features off. It just wasn’t doing the right things at the right time. I should add that they all loved their nests and found the ability to warm up the house on their way home really really useful. But the predictive things were making assumptions about their activities that were not immediately comprehensible by their users. And when the learning features were on the devices felt inscrutable to them, confusing and alien.

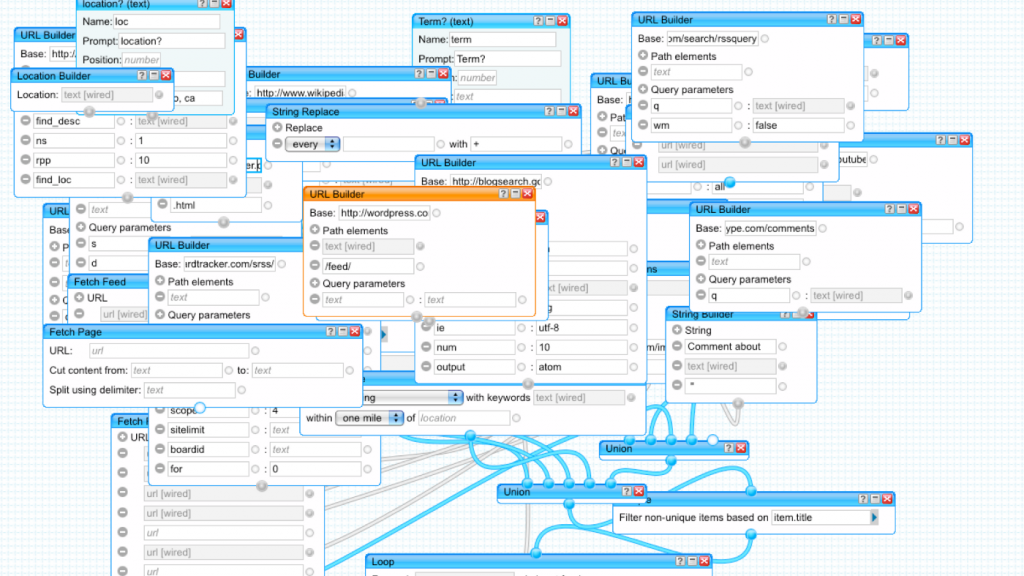

But if Nest’s interfaces aren’t perfect, at least they’re vastly superior to the other end of the spectrum:

This is an example of the UI from Yahoo Pipes, but honestly it’s the visual equivalent of what a lot of programmers I know are doing in their homes with IoT devices. It’s pretty clear this can’t be the direction.

It’s possible to simplify this kind of interaction with services like IFTTT (If This Then That), which let’s you set one ‘trigger’ and then ‘one response’ in a pretty simple way. But while it’s simpler to assemble, to make any complex situation you end up making lots of simple rules instead of one complex one. It doesn’t really make things much better. And that’s because even the simplest requests a person might make actually end up being much more complex than the first appear. For example, people say they want this:

But when you actually dig into what they actually want — when you take into account the various devices, people and contexts that impact how you’d like your home — you end up with something a bit more like this:

I genuinely think giving people all the power of a complex rules system, without bombarding them with UI complexity, is the hardest problem in the Internet of Things at the moment and the one most deserving of extraordinary mental effort trying to fix. All the power of these devices hides between interfaces and metaphors that are totally incomprehensible to normal people.

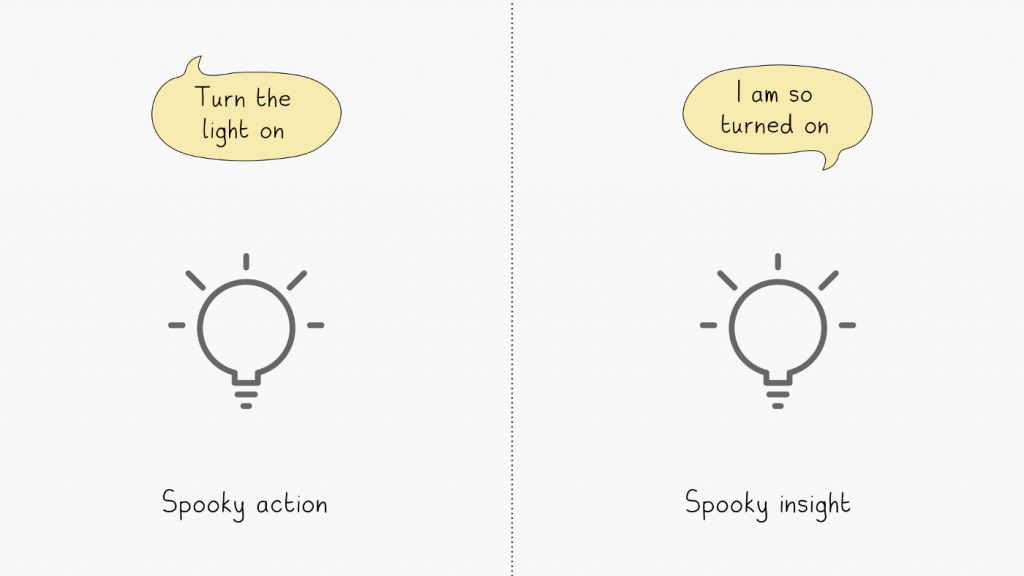

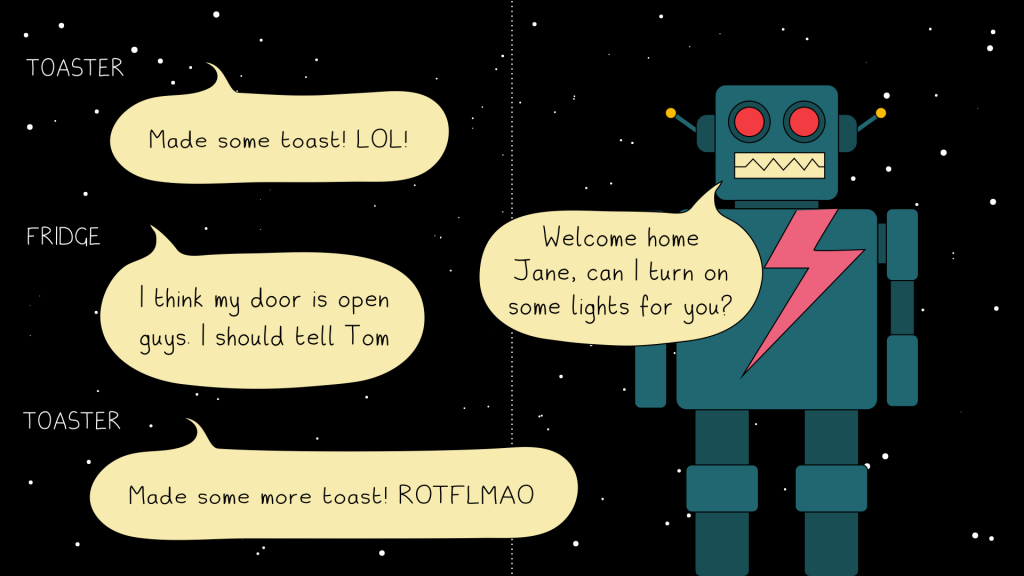

Finally, we get to number six. The ideal service layer communicates clearly and politely in ways that are timely and familiar. And this is I think super important, because at the moment a whole bunch of devices that we use are pretty much totally inscrutable and we don’t know why they did the things they did. And when they do decide to tell us things they do so by aggressively beeping or sending us notifications by the truckload. Finding the model that makes these communications humane and polite is one of the other largest challenges we face.

Personally I think the answers here lie in the work we’ve been doing to make communication between people comprehendible — our social streams might be a great metaphor for a world of communicative devices. But more on that shortly. In the meantime, here are my six principles again:

These are the principles that we’ve been working with when we’re building Thington — but I think they’re equally applicable to almost any software layer for a connected object you can imagine.

They are a set of ideas that I think represent a service layer way beyond the simple idea of a remote control — a service built with them could follow you across devices, across contexts, across the world. I really think this is the way that we should be working, the direction we should be pushing in.

Conclusion

So I’ve talked at length through this piece about the core directions I see in front of us now in trying to make a world of connected devices comprehendible to normal people. One is a common refrain among talented designers — that interaction should be embedded more into the physicality of the things themselves. The other is my own position, that this world at scale only really makes sense — can only really be intuitive — if we accept that a service layer exists, has to exist, is useful and important. I’ve also argued that we should push the service layer forward away from being something bland and slight like a universal remote control towards something deeper and more interesting.

With Thington in particular we’re experimenting with a couple of metaphors that I think really embody these principles and push them further in interesting ways.

Firstly we’re treating the way your objects communicate with you the same way that Facebook treats your friends communicate with you — with human readable chatty, social media-like streams of information.

And secondly we’re trying to replicate the feeling of a butler or assistant suggesting things he can do to make your life better. In doing so we’re trying as much as possible to take the complex rule-making systems away from the general user.

Obviously, I’d love it if you went to thington.com and had more in depth look at what we’ve chosen to do, but if you don’t have a chance to do that, here’s a way of representing what we’re doing that is pretty fun (even if it does make it look super ridiculous).

These are just our attempts to live up to the principles we’ve put together and build an experience that takes the service layer way beyond what exists at the moment.

This may resonate with you, or it may not. I hope it does. But even if you don’t agree with me on the specifics — even if you think that tangible interactions and embodied interaction are the future of every device on the planet — the one thing I really need you to believe and take away with you is that this world of connected devices one way or another is coming.

Every day more devices, appliances, sensors and actuators, homes and cities are coming online in one way or another, and this is going to have a transformative effect on the world.

I personally believe that the company that creates the service layer for the Internet of Things could be as significant, powerful and large as Amazon, Google or Facebook — only they’ll not be the way you interact with your friends, but with the entire physical world that surrounded you. We’re on the brink of a new service layer for the physical world that operates at a truly planetary scale.

And the design patterns and interactions for this world are being formed right now, by people just like us. And if we don’t get involved and design and think about the complexities of the world, then other people will, and when they do they’ll encode in them ethics, belief systems, views on privacy and intrusiveness, a sense of the role of network in the life of the individual that may be very different from the world we’d like to live in.

This has been a long piece, so it might be difficult to stretch your memory right back to the beginning, but if you remember, I referred to this alleged misquote by Thomas Watson, the founder of IBM.

When I read his line, I’m always reminded of Clay Shirky’s response, referring to the Internet.

To which I would add only add that every day, more and more, this one computer in the world is the world in which we live.

It’s massive, wild, distributed and it’s starting to break free of the browser and the app and permeate every aspect of our homes, offices and public spaces.

So this is the time to get involved, to explore this space and find better patterns, better interactions, better models of how the future will work. This is the moment where we as designers can have the most impact, helping to define a User Experience, an ethical, powerful, transformative UX at quite literally a planetary scale.

The world of tomorrow could be transformed for the better if we work to make it so, and I believe very strongly we have it in us to make it truly extraordinary. And that’s all I have.

Postscript:

If you’re interested in trying out Thington, go to https://thington.com to find out more and download the app. If you have any questions or comments, ping us on our Twitter account @thingtonhq or e-mail us at hi@thington.com and we’ll do everything we can to help you out. There’s a list of Frequently-Asked Questions on the Thington website too: Frequently Asked Questions.

If you’re a manufacturer or potential partner and you’re interested in Thington integration or want to find out more about what we’re doing, then e-mail us at hi@thington.com.

If you’re a member of the press and would like to talk to us then e-mail us at press@thington.com — there are also some resources for you available at https://thington.com/press

As I said at the beginning of this article, this talk was given originally at Webstock in New Zealand in February 2016. In this version I’ve removed a few of the jokes that only make sense if you know Webstock orNew Zealand very well. Having said that, if you haven’t been to New Zealand or to Webstock then you are really missing out and you should make an extra special effort to do so. It is my favourite event on the planet, the country is stunningly beautiful and the people are completely amazing. As always, thanks enormously to Tash, Deb, Mike, Ben and the Webstock audience for being incredibly welcoming and brilliant in every way.

The artwork in this piece was mostly drawn by Tom Coates in Adobe Illustrator, but the visual style of the whole thing comes from a beautiful piece of illustration by Chris Martin for Wired UK about setting up a smart home and my own efforts with the House of Coates twitter account. I loved the piece so much that I found a way to contact him online and I have two copies of it printed and framed — one in the office, one at home. My own efforts in this article are a bad pastiche of his extraordinary work, and I hope are received with the spirit they were created — as a statement of enormous respect to his creativity and a love of his style.

The typeface in the illustrations to this piece was made by Tom Coates in a weird little app for the iPad called iFontMaker. It is — as you might expect — based on a slightly stylized version of my handwriting. If you want to get your hands on it, please reconsider! There are much better typefaces in the world with a similar aesthetic. If I still can’t persuade you otherwise, I’m still working on all the special characters, and when I’ve done enough of them I’ll think about putting it out in public.

This material is in part based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number (1621491). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.