This is an exceptionally long post detailing pretty much everything I learned at an event shortly before Christmas at Meta’s offices in San Francisco. I’ve been delayed in writing it up because of traveling back to the UK for Christmas and other commitments – and because I wanted to capture everything. It’s roughly written, and I’ll probably edit it a bit after posting. If you have questions or comments or want me to clarify anything, DM me on Twitter @tomcoates or email me at tom [at] plasticbag [dot] org.

Just before Christmas I was lucky enough to be invited to a Data Dialogue event at Meta’s offices in San Francisco. The event was designed to reach out to people in the ‘Fediverse’ community, tell us their plans for their product “Threads” and get a bit of feedback about the policy and privacy implications.

Since that meeting, Mark Zuckerberg has announced the first part of the Threads roadmap – making it possible for people to see Threads posts within the wider Fediverse. Given that, I thought maybe it would be a good time to write about the other things I learned and some of the feedback we gave the company.

What is the ‘Fediverse’

For those of you who haven’t been keeping up, the Fediverse is one approach to the question, “How can we have one (or more) social network(s) that no one company owns, for which anyone can make a client or a server, with all of them interoperating as seamlessly as possible so that they’re understandable to people who aren’t terminally online”.

The main Fediverse approach is through projects like Mastodon – which are effectively small, local social networks that can be hosted by an individual or company, but whose users can still communicate with — and reference posts and people — using other similar networks. Most of these products are built with at least some reference to the ActivityPub protocol co-written by Evan Prodromou.

There are other approaches to this idea of a ‘public’ (that is non-privately owned) social network system or protocol. Some run on crypto tech, where people run ‘relays’ (some of which generate crypto currency for the people who run the servers in the process) but the individual user completely owns and maintains their own identity and isn’t ‘hosted’ as such.

I co-founded a company a few years ago – funded by Bloomberg and other VCs – focused on one of those (built on the secure scuttlebutt SSB standard). We made an iOS client called Planetary. Since I left the company it has changed its name and pivoted to another protocol. That’s why I was invited to this event. I’m not going to talk about that much, but feel free to ping me if you have any questions.

Anyway, there are lots of reasons why people should be switching to the Fediverse – among them:

(a) that one company should not generally be the main arbiter of what is acceptable speech for half the population of the planet;

(b) the general public should have the option to communicate with their friends (or find out information) without having that experience meditated by or optimized’ by algorithms generated by other people;

(c) there are reasonable questions that can be asked about whether or not a space entirely owned by advertising-focused companies can build products that aren’t socially corrosive or promote conflict and polarization.

However, there are also lots of reasons why people tend not to switch to the Fediverse – it can be challenging to understand so the process of using it presents a little more friction to the general public, some of the clients can be a bit clunky, and it’s often unclear how individual products within the space can support themselves financially. That’s why despite several big spikes in people leaving Post-Elon Twitter (I will not be calling it ‘X’) to join (in particular) Mastodon, the number of active users for the Fediverse has generally stayed in the low millions of people. That’s about 1/2000th the volume of the people who use Facebook/Instagram/WhatsApp etc. in any given month.

‘Threads’ and the Fediverse

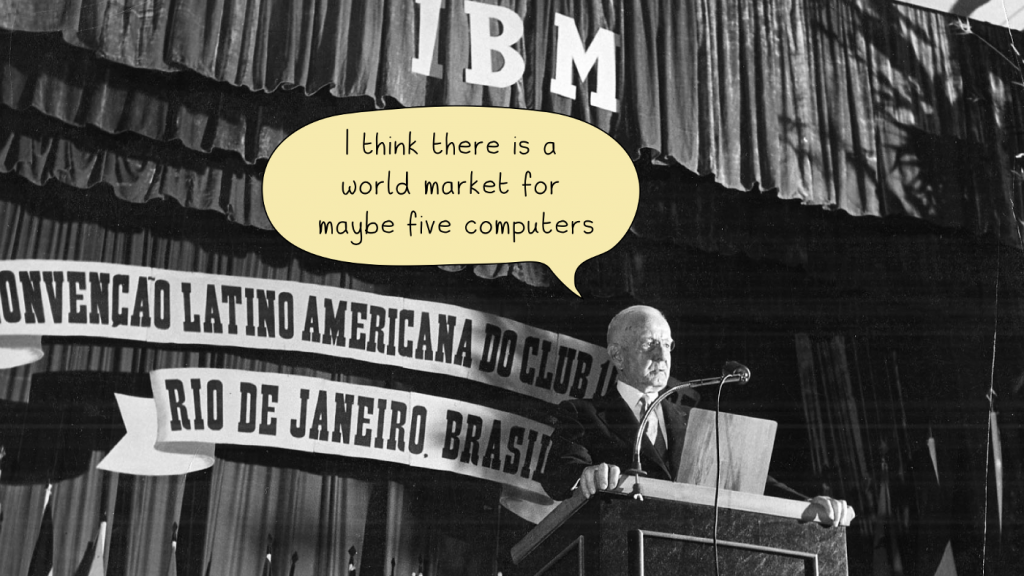

So it was both very interesting and also a little alarming when Meta announced Threads around eight months ago – and at their launch they made it clear that their goal was for it to be part of the Fediverse.

It was interesting because it seemed to indicate that something was finally changing in this space and that we could look forward to a world in which social networks operated a little bit more like e-mail – ie. used by billions of people, not owned by any one company, where you could choose your provider, but still connect with the entire world of other people.

And it was a little alarming, because the current Fediverse is mostly enthusiasts and utopian individuals operating in a mostly non-corporate environment, with few (if any) algorithms and little (to no) advertising. It’s currently a space where people don’t generally have to worry about the billion-people-impacting, market-driven and perhaps dehumanizing decisions of massive companies or the fetid whims of asshole billionaires. That has tended to make the spaces much less corrosive, far less aggressive and really quite pleasant to be in.

It’s not unreasonable to wonder if such an environment can withstand the arrival of a social giant.

Anyway, after some initial excitement and dread, after eight months the Fediverse community had started to calm down a bit – mainly because it seemed like this integration was never going to happen. After all, Threads has had a very successful launch – with around a hundred and sixty million people signing up over the last few months. It is a highly active space, and its active user base is now a hundred times the size of the Fediverse with which they had claimed to want to connect. Had something changed? Was it all a bit of corporate flim flam? Was it just an attempt to market it as a more palatable and distinct alternative to Twitter that they really had no intention of following through on? Or had they maybe just changed their minds?

Well, I can report that the answer is no. They have not changed their minds. They seem to be very keen to continue to integrate Threads with the Fediverse. And at least superficially they seem to be attempting to do so carefully and in good faith.

I have some more behind the scenes stories further down this post which I’ve heard from various players on the edges which might explain some of the motivations at the company, plus a bunch of speculation from other Fediverse attendees. And I have some concerns and questions about what they’re doing and how – both in terms of the impact I think it could have and also in terms of how it will be received by the community more widely. I also have a number of significant concerns with the Threads project itself.

But I can report that in my opinion the teams building it and the integration seem to be decent people, trying to build something they’re excited by, wanting to be part of something new and truly federated, and wanting to be respectful and careful about how they do it. And whether or not you think their arrival in the space is a good thing, that apparent good faith and care has mitigated at least some of my concerns.

Okay, so let’s get started with what they announced. One (hopefully final caveat), the whole thing was run under Chatham House rules, which means that I can talk about everything that happened at the event but I can’t ascribe what was said to specific people without their explicit permission. To anyone else reading this who was in attendance, you should feel free to quote me on anything I said. If you’re comfortable being attributed for anything below, then let me know (via Twitter or e-mail tom [at] plasticbag [dot] org and I’ll amend the post accordingly.

The Product and the Roadmap

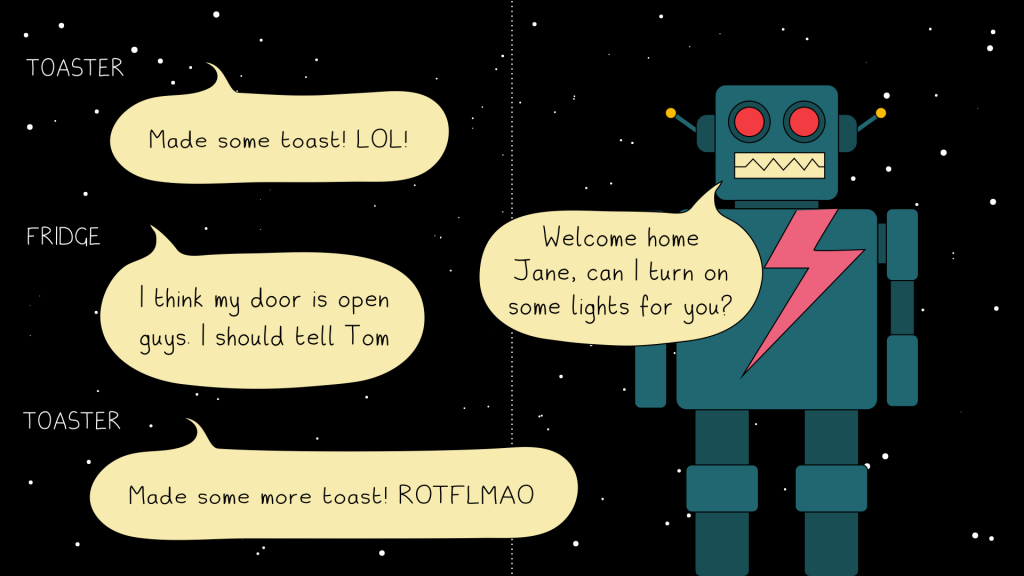

The first part of the session was focused on what their goal for Threads was and what the roadmap looked like. They started by stating the product was “a text based app for public conversation and to share your point of view on real time events” (so effectively a Twitter-clone, which we knew), where you could have “productive conversation and tune out the noise” and that it was important to them that it was “open and decentralized”. They seemed quite committed to the latter, explicitly saying things like “Threads will help people find community, no matter what app they use” and “If you don’t like the rules we are enforcing on our server, you will be able to take your followers elsewhere”.

I have some thoughts on that, which I’ll talk about later in this piece, but before that let’s talk about the roadmap they laid out, which is as follows:

• December 2023 – A user will be able to opt in via the Threads app to have their posts *visible* to Mastodon clients. People would be able to reply and like those posts using their Mastodon clients, but those replies and likes would not be visible within the Threads application. Threads users would not be able to follow or see posts published across Mastodon servers, or reply to them or like then.

• Early 2024 (Part One) – the Like counts on the Threads app would combine likes from Mastodon and Threads users

• Early 2024 (Part Two) – replies posted on Mastodon servers would be visible in the Threads application

• Late 2024 – A “mixed” Fediverse and Threads experience where you will be able to follow Mastodon users within Threads, and reply to them and like them

• TBD – Full blended interoperability between Threads and Mastodon

Now there are a few bits in here I think are really interesting. Many of them make a lot of sense, but I still think will be controversial.

The first is how long this integration is going to take and where they’re starting work. I imagine there will be a bunch of people out there who think the early stages above feel like Facebook is ‘engaging’ with the fediverse in a pretty selfish way – ie. the first stage seems pretty one-sided, with Facebook pushing their content into other people’s servers, but not reciprocating.

This feels neither completely fair nor completely unfair. My first sentiment was similar – to what extent is this an integration rather than a colonization? You could view this as Facebook attempting to erase the fediverse – to take it over. After all, it’s unclear what the fediverse gets from having hundred million Facebook users pushing their content into their space without any ability to seriously reply and engage with them.

I still think that this first stage is likely to be the least popular and will drive the most discussion of Meta and whether they’re engaging in hardcore extractive and exploitative capitalism. I suspect many in the Fediverse will find this first move pretty repulsive.

On the other hand, I’ve worked in large companies. And I’ve worked with privacy and policy teams in complicated new areas (I built a product called Fire Eagle a million years ago which was pretty much the first one to handle user location data, and that triggered a good amount of terror among Yahoo’s privacy and compliance teams).

And I’ve also had a (fairly sporadic and not always effective) place on the advisory board of the UK’s Open Rights Group. I know how hard this stuff can be and the dangers in the data and the space. Meta will have to deal with a lot of regulatory questions and privacy concerns before they can launch anything, they will have to figure out how they can engage with content and users who never signed up to their TOS and privacy policies, they’ll have to figure out what impact that will have on their other systems and business units, and they’ll have to develop a sense of the issues that campaigning groups, the FCC and the EU are likely to have with this new development. All of this stuff is a Big Deal.

For me it makes sense they’d take this stuff slowly and carefully, and it also makes sense that they’d start off focused on what functionality they can offer their users who have signed up and opted in, before they start confronting the larger issues. It’s really the only way they could progress. And I guess they’ll just choose to suck up any negative response they get as a result.

I want to be very clear here – whether or not the way Facebook/Meta/Threads choose to handle this ends up being ethical or appropriate is really anyone’s guess at this moment – and I’m sure a bunch of people reading this have their suspicions that it won’t be. However—ethical or not—I believe they’re going to be very focused on being legally compliant and very conscious about avoiding (as they see it) the threat of further regulation. People often think large companies are more cavalier with the law than small ones. I can assure you in my experience exactly the opposite is the case. Large companies are mostly much more cautious about breaking the law, and instead invest much more of their money in trying to change the law in their direction. But that’s a story for another time.

Back to Meta’s roadmap: this project is also intensely technically difficult of course. It’s worth remembering that they didn’t build Threads out of pre-existing Mastodon open source code and they didn’t start with ActivityPub as a basis. They built it out of the Instagram codebase and community with a view to expanding that one network into this new parallel open and distributed space. As such, a bunch of core concepts and technical decisions are not directly and immediately compatible and will have to be rebuilt or redesigned to connect amicably.

By the way, as someone who has built large products for a number of companies—including the BBC, Jawbone, Nokia and Yahoo, and run two start-ups—I have to tell you based on my limited knowledge at this point I think this roadmap is probably wildly optimistic. But I guess we’ll see.

Who was in attendance

Before I continue, I want to give you a sense of the people who were at this meeting. If I had to guess I’d say there were roughly twenty people present, falling roughly into three chunks – the first third were representatives of the Threads team, the second a group of legal, privacy and policy representatives from Meta and the rest of us were sort of roughly ‘representatives of the Fediverse’.

As is probably obvious from a community that is specifically and self-consciously uncomfortable with monolithic organizations and wants to find a way for lots of smaller groups to cooperate, the Fediverse group was not particularly unified in our responses, nor were we representative of the ecology as a whole. There are a thousand projects and hundreds of talented and interesting people with more or less impact on the space.

Still, some of the people present did have very, very really deep and long-standing engagements in Fediverse and ActivityPub projects. One of them said that of probably the ten most significant people trying to corral the space at the moment, three were in the room. I want to make clear that despite my deep interest in and work in the area I’m almost certainly not one of those three.

So, both a pretty serious group of people but also not representing the full range of opinions and views in the space. As ever, none of us can speak for the whole community. In fact at this point that would slightly miss the point.

Why are Meta doing this?

Anyway, despite our different perspectives, one question was clearly on everyone’s minds – Meta had talked about what Threads was and made it clear that openness and interoperability were key to the project – but they hadn’t talked about why they were doing it?

What on earth was motivating them to make this thing so – in theory – open?

Their answer was that they simply felt it was the direction of travel for ‘social’ generally – that the area had been growing steadily, particularly post-Elon’s takeover of Twitter, but that they’d also had a lot of conversations with high profile people who build communities on their platforms and they were increasingly uncomfortable with Meta or Facebook or Instagram effectively owning their followers. They were looking for the ability to know that if they needed to they could move elsewhere.

I’ll be blunt – I didn’t find this enormously convincing but it was interesting and I’m sure there’s some truth to it. It just didn’t feel like the whole story. We asked about the business side of things and they said obviously they were a business and moreover an advertising business, so probably that would be the way they made money in it long-term, but it wasn’t happening for a while. The representative said something along the lines of, “obviously we have a business model, and it’s fair to ask how this squares with that; the answer is we don’t actually know; there will likely be ads but not in the near future.”

After the event many of the Fediverse representatives speculated about other motives. They varied between the following:

1) Meta thinks Twitter’s part of the zeitgeist is important and powerful and are interested in that space – and they’re following Google’s response to the iPhone by promoting an open competitor they can benefit from;

2) Meta is concerned about greater regulation and are building out a space that perhaps they can still dominate but which they can make absolutely clear remains open, in order to shut down arguments (particularly from the American right) about how they’re censoring conservatives (they can move elsewhere) or antitrust laws (we’re directly creating an open environment where people can switch easily);

3) Someone down in the hierarchy doing a PM job just added in Fediverse support as a line item in a pitch deck to act as a differentiator and it’s just risen up through the ranks somehow surviving each time because many people simply didn’t know what it was. And now they have to build it;

4) Mark Zuckerberg just hates Elon and is just doing everything he can to destroy Twitter.

I have absolutely no idea which one—or combination—of these is most accurate, but I can report one interesting story that I’ve now heard from two separate sources, one in attendance at the event and another friend in another part of the industry. According to both of them, at a hack day inside Meta someone presented this concept and a rough working prototype and said it was really interesting and exciting and that they should work on it and that it should totally be open, and that person, bizarrely, was Mark Zuckerberg himself. I have no idea if that’s true, but it’s certainly interesting and it would explain a lot of the enthusiasm for the venture inside the organization.

Anyway, I don’t think that’s necessarily incompatible with the motivations above, but I did think it was interesting. Come to your own conclusions, I guess.

(A note on that: I have many issues with Mark Zuckerberg’s approach to things—he’s definitely focused on business as the first priority and social responsibility is … well, it is somewhere on the list I’m sure—but he’s an intelligent man, and an engineer, an investor in some early decentralized and distributed social tech and someone who attended, with me and many other peers, social computing FOO Camps, organized by O’Reilly Media in the early days of the social web. He knows about ActivityPub and all of these open standards and has done for years. So if he’s the one who was pushing for it – I guess I’m not surprised! What’s more interesting – and actually quite exciting – is that he thinks this might be the future of the social web!)

Godzilla & the Fediverse

Now, I mentioned above that the people we met at Meta seemed like decent, well-intentioned people attempting to do the right thing. However, this may not be enough to be a ‘good citizen’. And to understand why I think it’s worth talking briefly about the scale of the various parties.

The community that Threads is planning to participate in is that of Mastodon servers federating with one another via Activity Pub. The estimates of this community are that there are about 9,500 separate mastodon instances participating in this ecology, with roughly 1.5 million Monthly Active Users (MAUs). This is a fairly substantial number but of course it pales in comparison to Meta more generally, which has closer to three billion active users. Or to put it another way, Mastodon users represent about 1/2000th of the number of people using Facebook/Instagram/Threads/WhatsApp etc. worldwide.

Threads itself has only been around for a few months now and it still towers over the rest of the Mastodon community in terms of users. It’s based on the Instagram user base, and Instagram users can opt in to use Threads with a single tap. Because of that—as of a recent earnings report—Meta can currently claim around 160 million total users and about 100 million MAUs for Threads alone. So, again, maybe we shouldn’t be thinking about Threads ‘integrating’ with the fediverse and instead think about Threads attempting to engage with the Fediverse without entirely crushing it in the process.

Effectively you can think of the existing Mastodon / Fediverse community as a pretty decently sized US city of people, with each server being a separate building within it. Meanwhile, Threads is an apparently friendly version of Godzilla, hundreds of times as tall as the nearest building, wanting to say hi to people, but every time it makes a move, there’s a risk its tail will kill thousands.

Or perhaps it’s more like the spaceships from Independence Day, only—you know—trying to be nice. It’s not hard to imagine that however well intentioned they’re going to be, their presence is going to be absolutely enormous and potentially catastrophic.

Anyway, I mention all of this scale because I think it’s really important to keep it in mind when thinking of other issues that came up at the event – including how content moderation is likely to work, what kind of public education work they need to do, and what the rest of us need to think about in order to make sure that their arrival actually does open up social media, rather than completely destroy the independent communities that already exist.

Content moderation

So let’s start off by talking about Content moderation. This was an issue that came up regularly during the day. Clearly, Meta moderates its own content on its own servers and will reserve the ability to remove that content and ban any user it wants. That is unlikely to change.

However, the Fediverse presents some interesting challenges here. The goal of integrating with the fediverse is specifically to have Meta users’ content appear in someone else’s mastodon instance, and vice versa.

This definitely appears to be an area that is causing them some concern and confusion – and they don’t seem to be 100% clear on how to handle it. For a start, all their users opt in to using Meta, but third party users do not. Nonetheless from the discussion it seems obvious that they’re going to have to reserve the right to exclude content and users from being cached on their servers or from being visible in their app if it breaks their rules even if it originates in another Fediverse instance. The same will presumably be true the other way around – individuals in public will be able to ban Meta’s instances from engaging with their instance or ban or block abusive Meta users.

One conversation that emerged around this was whether there was a way that Facebook could usefully open up these decisions more widely to benefit the larger community. This is an idea I’ve been keen on for a while – that an entity that is doing moderation work could open that up as a service which third parties could subscribe to. This might be a way that smaller instances could actually benefit from Meta’s presence, resulting in a better moderated space overall.

Of course the negative side of that is that Meta is not actually known for being particularly rigorous in their moderation, and in fact only has around one moderator for every 100,000 users last time I checked. Plus of course, this would entrench their already vast power as the arbiter of what is acceptable or unacceptable speech on the internet even further than it already has been. So, there are some significant risks.

Bluesky’s content tagging was mentioned during the day – they appear to have a system whereby reported content could be marked – to be crass – as more or less ‘offensive’, and then the user gets to choose what they want to see. If you’re comfortable with slurs like the n-word or the f-word being used between members of each respective community then – in theory – you could indicate so. If you weren’t comfortable with it then your community could choose to filter it out. If you wanted full access to everything no matter how vile or offensive you could choose that on your end.

There’s an obvious possible extension of this kind of approach in a distributed environment, with one (or later more) parties tagging the content, and each instance choosing what limits it placed to content visible within its bounds. I think this is a very interesting approach, and one I’d really like to see people develop more – perhaps every Mastodon instance has a plug in, subscribes to a moderation server, and pays some money towards moderation based on the number of users they look after. In return, they get a fully moderated environment, and they can tailor their settings as to what can be seen on their instance. We’re not there yet, but it’s an interesting future direction.

Another question emerged regarding users moving their content off Meta’s servers. I mentioned this possibility above – that Meta was aware that people wanted ownership of their communities, and to be able to move them to another server if they didn’t like Meta’s content moderation or monetization. An obvious question that emerged was whether or not a user who had been banned on Meta should be able to export their content and users and start up again elsewhere on their own Mastodon server. Again this appeared to be a conversation that they hadn’t quite dug into yet, but the sense I got from that was that they’d end up saying that was acceptable, but the banned user’s content would still not be visible inside Threads no matter where else they went.

Identity systems and educating the public about the Fediverse

One conversation that emerged was about the current way in which identity works in the Fediverse. Generally it’s a bit like an e-mail address. If you have your content on an instance running at example.com, and your user name is @tomcoates, then your full identity is (@)tomcoates@example.com.

In order to make this work with the whole ecosystem, each instance (for example Threads) needs to ‘federate’ with others, or index people’s identities from different places so when someone wants to write a post that mentions me, the client can look me up and help by autocompleting my identity. Otherwise you have to know the full address of everyone you’re talking about and that’s probably beyond most of us.

This presents a few obvious questions for Threads – (a) whether they’re going to index everyone’s identity across the whole ecosystem, which could cause some problems and (b) whether or not the general public will understand the way these addresses are constructed. The indexing obviously presents some data retention issues – how do people opt in to being indexed? What are the legal implications. This stuff comes up a lot in these discussions – with search, identity and algorithmic timelines all presenting data use questions. And it’s clear that without it—and even potentially with it—this user addressing style is likely to confuse the hell out of people.

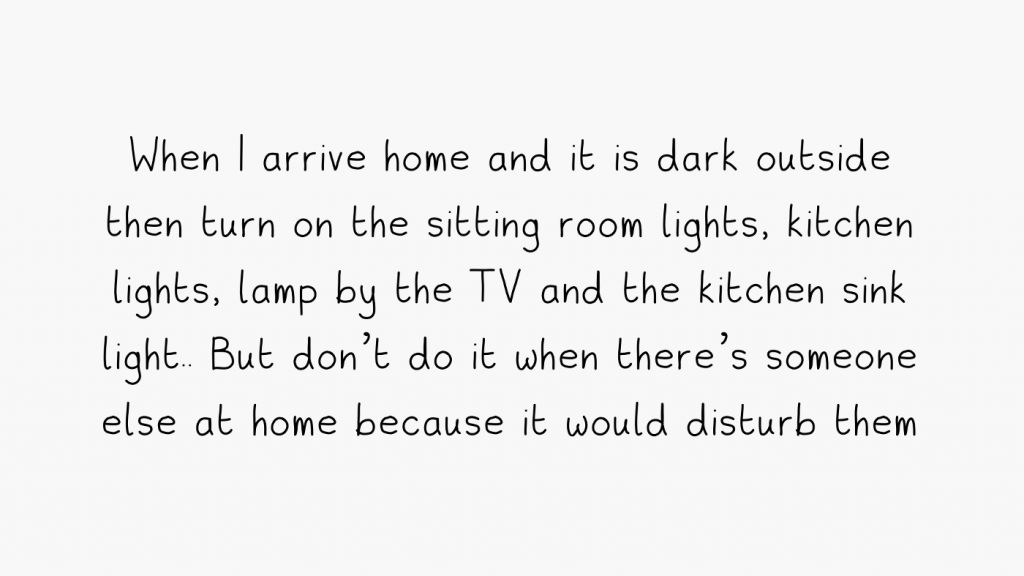

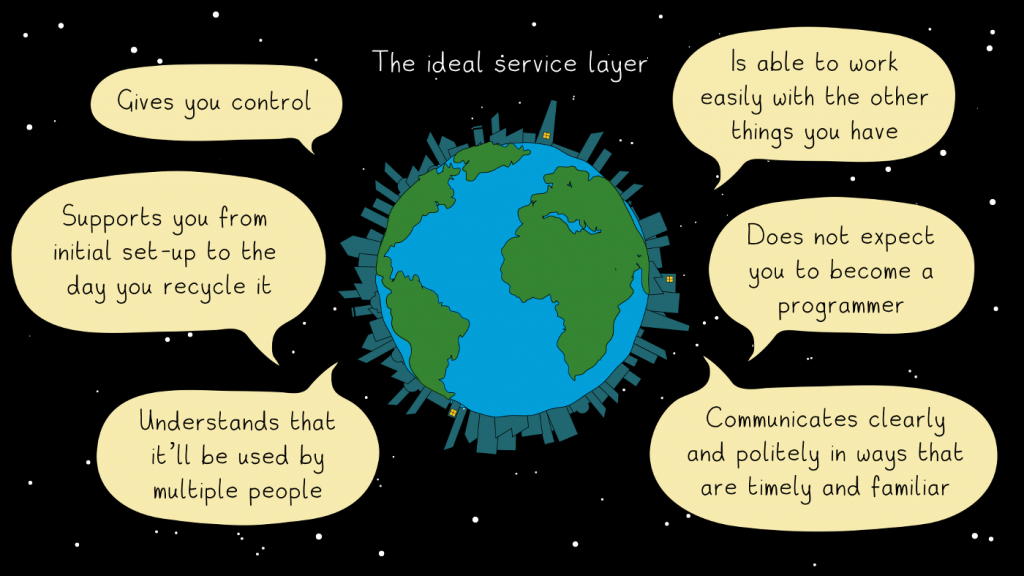

This led to various other conversations and ideas – whether or not it was Threads’ responsibility to educate people about how the system worked more generally (for example – does a user know that your content will be cached on other servers which other people may run ads against, or how the identity system functions) and whether or not other identity systems should be created.

One option presented that has been talked about a bunch recently was using a domain name as an identity, one separate from the service you were currently using to write or consume your content. A common response to this was that this was another step into confusion and complexity. Others argued that it was impractical to try and make Threads take on the responsibility of explaining things to people and to hold their hands through the whole process, and that people would just gradually pick it up and come to understand it over time.

I want to argue exactly the opposite – that a service like Threads is very clearly going to have to explain to people how this all works. They’re going to have to find a way to make it understandable and ideally simple to the general public. And the reasons for this are twofold – regulation and bad PR.

They’re going to be legally required to write a reasonably clear Terms of Service document and Privacy policy that articulates exactly how everything works. And if the public end up not understanding what is happening, then the next time they’re hauled in front of regulators in the EU or in the US Congress they’re going to find themselves in very hot water.

I’ve written documents before explaining to people how decentralized systems work and what happens to your data and content. They are not easy things. The concepts surrounding them are tricky. It is hard to do it well. The hardest bit is to explain to people precisely how everything works (which is not that dissimilar from e-mail) but to make it sound as non-threatening as it generally really is. You have to explain to people that if you write something, it may get cached on someone else’s server and may never completely be erased from the internet, without scaring them. And explaining that the same is true of writing a post on Twitter or Facebook doesn’t generally help.

I think I’ve done a decent job of these explanatory documents in the past – I’ll post an example at some point in the near future – but it is tricky. Nonetheless, it simply has to be done.

But it’s also not such a hard thing to do. It is within the scope of human endeavor! Every single concept we take for granted today regarding the Internet and how it works was initially confusing as hell. Web addresses, cookies, user accounts, secure sign-in, privacy policies, user moderation rules, private/public accounts, using browsers, setting up e-mail, that if you send an e-mail you can’t then delete it. All of these things are things people have had to learn, and all of them started off quite hard for a member of the public to get their heads around. It was education, good interface design and clear instructions that got us to this point. And none of that will change. If Meta tomorrow set up an identity system where you chose a user name and a TLD and they said, “now you’ve made an identity that you can to login to a thousand different services” then people would start to get the hang of it.

Still, it’s annoying work that adds friction and the general public will almost certainly start off being confused by it. Frankly, if there was any area that Meta could really help everyone with, it might be by putting its weight and presence into getting its three billion users up to speed with how the Fediverse works

Personalization and algorithms

When you sign up for Threads and follow some people, you do not by default then get dumped into a reverse chronological list of the posts they’ve written. You end up in a space that’s very similar to Instagram’s algorithmic feed. That is to say – your feed will be a mix of particularly ‘good’ (as determined by the algorithm) posts from the people you follow, mixed in with other posts from other places that the algorithm thinks you’ll like (read: engage with).

I’ve been thinking about this stuff or a while, and I have some fairly strong opinions on it. The conclusion I’ve come to is that this kind of approach is absolutely great for entertainment-style products, but actually very dangerous for news-based or informational products. TikTok is the prime example of an entertainment style product, as perhaps to a lesser extent are YouTube and Instagram. These products simply track what you watch or like and then deliver you other things that you might find delightful and interesting. A good proportion of the time the recommendations are at least fine, often they’re brilliant and 99% of the time the choices they make have little to no impact on your life or environment.

This simply isn’t true for informational or political content. In these situations the algorithm is quite capable of heavily influencing someone’s opinions and views and distorting their view of the world in a way that damages our ability to function as citizens – simply by choosing what content is put in front of them. My ‘For You’ section on Twitter is relentless in pushing right-wing messaging and commentary, even though I have no interest in it whatsoever. This is probably because I spend a bunch of time angrily debunking the worst excesses of it. The same tricks that feel honorable and positive and fun in an entertainment context (choosing things it things will get a reaction and engagement) start to feel a bit more sinister in news and political content – like the algorithm its optimized for generating fights or controversy or clickbait. It feels nasty and risks promoting division or conflict.

Meta thinks that Threads should not be fundamentally used for political commentary, but bluntly good luck enforcing or influencing that. And if it’s going to be used for those things then the presence of the algorithm is – in my opinion – a problem.

Various people spoke up about the algorithm during the meeting although it’s possibly fair to say that none of them were quite as exercised about it as I am.

I feel quite strongly that at the very least the user should be able to choose whether to use an algorithmic timeline or not, in a clear and easy to find way, without it automatically switching back after a period of time. There are some ways you can make this work in less dangerous ways – showing ‘highlights’ from your feed but giving the option to see everything for example, or having a separate algorithmic and reverse chronological feed that a user can switch between easily. And I would strongly recommend that Meta switch to one of these approaches.

In the meantime there are some very specific issues which came up during this session which are worthy of a mention – one in particular was whether or not content from third parties in the wider Fediverse should be part of this algorithmic feed. “Would they expect it?”, was one comment. “Would they be horrified by it?”, was another.

I actually think this is a little more complicated than it initially appears – and again gets to the necessity of creating databases about people who have not opted in to Meta which I mentioned above. For Meta to be able to do recommendations of third party content means doing some kind of analysis and indexing of that content – ie. creating a profile of a user who never signed their TOS with information about them and who to recommend their content to. Quite apart from whether or not people are comfortable with that, I’m not sure what the legality of that might be from a (in particular) European GDPR perspective. I suspect if they’re careful it will be legally okay, but it still slightly sets my teeth on edge.

The final workshop

The last thing we did on the day was take a few significant groups – instance owners, Meta users and third party fediverse users – and break into work groups to answer a few questions, which I managed to rapidly capture. They were as follows:

- What do you think your group’s core expections are for their experiences in a federated social network environment?

- What do they expect of Meta vis a vis data collection and use?

- Are any of these expectations mutually reinforcing? Are any in tension with each other? Do they introduce any new or additional risks eg. to privacy, safety, free expression

- How can meta be considered a ‘good citizen in the fediverse’

I’ll be honest, these sessions were too short to be particularly useful, and I don’t know that we came up with much that was particularly interesting, but I thought it was worth posting the questions Meta were asking to give some sense of how they are at least at the moment trying to be decent citizens.

Other questions

Before I wrap up, here are a few pithy questions that people presented and the answers that Meta came back with, for the sake of completeness.

Could each person’s feed have an atom feed so people could subscribe without using the core app?

The general sentiment in the room was effectively ‘we don’t know’, but my guess would be the answer will eventually be no.

Would the content from third parties using Mastodon be presented as equivalent to the ‘native’ content or would it be like Apple’s blue and green iMessage bubbles?

The sentiment here was again – don’t know. Work in progress. But people obviously were keen to make sure that users understood what they were looking at.

Should Meta lead or follow in the development of the commons or the standards?

The opinion here was that it would be best for Meta to be involved but do not want to do it alone. “The real goal is not for it to be lead on all of the issues which are issues across the fediverse”.

Conclusion

My sense after this meeting was that Facebook are seriously interested in integrating Threads with the Fediverse. They do not want to crush the Fediverse. They perhaps think the future is a few large companies maintaining clients in a shared social space, where there’s also a long tail of other independent clients. This is going to weird out a bunch of people but it’s a goal I also share, so I’m okay with that. It’s worth saying that I want this world because I think it is a realpolitik alternative to one large company owning everything. I think a multi-client/company/instanced system like this would be better than now and solve a bunch of problems. But is it the utopian vision of how the world could be if we didn’t live in quite such an extractive system? Nope.

Back to Meta – I think they’re trying to engage positively, but I think that is going to be very difficult for them given the size of their userbase compared to the tiny environment they want to connect with. And I think they’re desperate for – and need – some bodies or organizations that represent the interests of the fediverse more wildly with whom they can coordinate standards and listen to desires for technical change, and can stand up for the interests of all parties. Such an organization doesn’t exist yet. Perhaps someone needs to start one.

All in all though, despite some very major misgivings here and there, overall I came out of this event much more sanguine about the way this is unfolding, a bit more optimistic about the future of the decentralized or social web, and interested to see where things go from here. I suspect we might see someone from Google or the BBC or Yahoo or Microsoft or LinkedIn make a similar move in the not so distant future. Who knows? Maybe we’ll get the interoperable shared, open social web that many of us have wanted for the last twenty plus years? Wilder things have happened. Fingers crossed?

Thanks for reading. I know it’s long and needs some editing. If you were there and want to be explicitly mentioned as an attendee, let me know – again on @tomcoates on twitter or email at tom [at] plasticbag [dot] org. It’s worth restating that these are my notes and represent what I understood from the day, and that I may have misheard or misunderstood some of the sentiments expressed. If you were there and think I left out anything important or misrepresented anything, let me know and I’ll consider a correction. Hope everyone’s having a nice day. Yours, xx Tom