This post concerns an experimental internal-BBC-only project designed to allow users to bookmark, tag and rate songs they hear on the radio using their mobile phone. It was developed by Matt Webb and myself (with Gavin Bell, Graham Beale and Jason Cowlam) earlier this year. Although the project is a BBC project, all the speculation and theorising around the edges is my own and does not necessarily represent the opinion of my department or the BBC in general.

We have more television stations than we have time to watch, more radio programmes than we can fit in analogue frequencies, more music and film availablethan any human could consume in their lifetimes and a huge ever-growing world of information growing every day on the internet. And this is just the beginning. The next push is the archive – decades of programming coming online, lost films recovered, libraries being digitised. But the scale of even this content is dwarfed by the third push into the world of the amateurised content-creator, where potentially billions of people are putting information and media out into the world as a matter of course.

The most substantial challenge to technology creators, media creators and distributors is – then – to find ways of making this enormous and every-growing repository navigable and sensible to real people. There are substantial rewards to be found in finding ways to help people find their way around this space – and people familiar with the challenges of the web over the last ten years are in exactly the right place to work out what these navigable mechanisms are likely to look like. But you don’t only have to create the navigation to reap the rewards – the organisations that can supply the right metadata, supplementary and structured relationships about and around their media will be the ones that will survive most easily inside this new ecology.

There’s also one more major challenge. Current media distributors and large-scale media creators are going to find themselves suddenly operating in a market of peer creators, where hundreds of people can create and interact and respond to the media around them. The network is already a challenge to broadcast – people who use the internet a lot use television less – but this is a new challenge. It’s a challenge of participation – where one-to-many broadcast-style content has to figure out how to find new ways of getting their ‘audience’ involved. This is a challenge that’s all over the place – and it’s a problem of bandwidth. How does one show or product or team respond to and respect the input of hundreds of thousands of individuals, and reflect it in what they make? If you’re last.fm it’s easy – you give everyone something different. But if you’re a popular content creator with one outward channel that’s the same for everyone, things get a little harder. How will they adapt?

This is the world that a few of us went to ETech this year to talk about. Mr Biddulph and Paul Hammond talked about BBC Radio’s current offerings and live work, particularly digital radio, on-demand streams and RadioPlayer and the famous Ten-Hour Takeover. Meanwhile Mr Webb and I talked about some more experimental work we were doing (in collboration with people like Gavin Bell) on the assumption that navigation, interaction and user-creativity were the core media issues of the next twenty years. We talked particularly about two projects: Group Listening and Phonetags. At the time, I promised to post something about the latter project at the time, but I never got around to it. After renewed interest from the FooCamp crowd, I thought I’d do it now.

Radio networks have always been interactive, but they suffer from bottlenecks. If you ask people to vote in a poll and then report the results, then you are to an extent reflecting your audience on air. But it’s a fairly homogenised and averaged-out view of their beliefs – pushed through a fine-meshed sieve. The variety is completely lost in the aggregation.

On the other hand, if you want to get some of the spice and individuality of the individuals concerned you can pick out specific individuals from your audience and put them on air (or mention them). Unfortunately, many individuals find the prospect of being on air more than a little intimidating – and of those that don’t, still only a fraction can actually be featured on air.

Both of these approaches have worked perfectly well for many years – but we’re now at a point where we can start thinking beyond them. So the question now is – what is beyond aggregation and lottery? What new patterns of interaction can we form around and within broadcast now that we have a networked world to hybridise with it?

Phonetags is an experimental project designed to try and help us get some purchase on some of these questions. The best way to describe it is to start off with some Principles for Effective Social Software that we developed as a result of working on the project. I’m not going to pretend that they cover everything, but they’ve proven very useful for us. We believe that for a piece of Social Software to be useful:

- Every individual should derive value from their contributions

- Every contribution should provide value to their peers as well

- The site or organisation that hosts the service should be able to derive value from the aggregate of the data and should be able to expose that value back to individuals

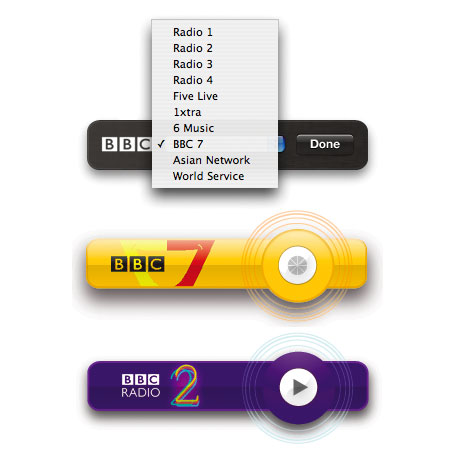

So this is how it works. Phonetags is about bookmarking songs you hear on the radio using your mobile phone. The way you use it is very simple. If you’re listening to a radio network (initially BBC 6 Music) and you hear a song you’d like to make a note of, you pull out your mobile phone, type an ‘X’ into an SMS (remember: X marks the song) and send the text to a BBC short-code. Later when you come to the site, you type in your mobile number into the search box to see a list of all the songs that you’ve bookmarked:

As you’ve probably already noticed, bookmarking isn’t the only thing you can do with Phonetags. You’ve typed in the ‘X’ to bookmark, but you can type in other stuff too – any words you type after the X are considered tags in the same style as Flickr and del.icio.us. You can navigate your own tags and explore other people’s tags – both in aggregate and individually as you see fit:

You can probably start to see in the latter screenshot why this stuff starts getting so valuable for us, at least. Those keywords – along with their reflected popularity – are starting to provide a pretty clear articulation of what the concept of ‘rock’ means.

Alongside the bookmarking and the tags, we added a new concept called ‘magic tags’. Basically these are special tags – like magic words – that perform some action upon the song that you’re bookmarking. At one level you could view them as nothing but compensation for a lack of UI widgets in an SMS interface, but there could be value in having tags that were both semantically interesting and also performed an action of some kind.

The tag we used in this circumstance was a simple ‘rating’ tag. If you wrote a tag of the form *one, *two, *three, *four or *five, you would mark the song as having been rated one-five stars for quality. This seemed to make a lot of sense in the music space, as it’s something people are familiar with from applications like iTunes, and you could imagine a range of circumstances where people might wish to express their opinions on songs played.

This view results in my favourite view in the entire system – that of the top-rated songs for any given ‘tag’:

A page like this exists for every tag in the system – there are pages of the top rated indie songs, pop songs, guitar songs, summer songs. You can imagine a whole range of possibilities for extending these pages to make them permanent or to atrophy with time / create weekly charts. It’s a huge mine of interesting musical information and a great way to discover new songs.

Anyway, the point of Phonetags was to try and find a different way for a user or audience member to participate in programme-making and to collaborate with one another without any of their contributions being lost, and with the value accreting over time.

In this model, a user gets value from their very first contribution – by having a song bookmarked that they can return to later. They gain extra value by being able to keep track of and comment upon the songs that they’re listening to – and when they do so, everyone else starts gaining value as well.

The peer benefit is in music discovery and navigation. There’s an incredible amount of new music being produced all the time. Our increased access to it means – in principle – that we should be able to find music that we felt more appropriately suited us, but the sheer volume makes it hard to explore. With a service like phonetags, an individual can start exploring music by axes of quality, or by keywords or by discovering people with similar tastes to themselves. And it gets updated in pretty much real-time.

Radio DJs gain a little bit of this experience too, in that they’re able now to operate as a peer in this exchange – tracking a bit more rapidly how well people are responding to songs, and using the live site as a way of mining for songs on any given theme (give me ‘happy’ songs, songs about ‘summer’, songs about ‘mum’, songs about ‘fruit’). They can also court reactions from their audience – rate all the songs in this week’s shows and we’ll play the best at the end of the week…

But it’s behind the scenes that I think the most substantial value could be created. We’re getting in incredible metadata on music that we simply didn’t have before – metadata and descriptive (emotive!) keywords that we can analyse and chop up and use as the basis for all kinds of other navigational systems. This is metadata that is often sorely lacking and could help us enormously in the future.

Anyway, I’d be delighted to hear any comments or thoughts that anyone has on Phonetags. All the images above can be clicked on if you want to see a larger version. If you want to contact me, then it’s tom {at} the name of this website (as usual). At the moment, we’re testing this particular version of the service inside the BBC (it’s available to all BBC staff to use so if you want the URL, then just let me know). The project is unlikely to be released to the public in its current form – but we’re using it as a way of testing out some of these concepts and approaches – some of which will probably manifest in upcoming products in one way or another.

And just to give you the disclaimer one more time: Phonetags was developed by Tom Coates and Matt Webb with Gavin Bell, Jason Cowlam and Graham Beale. However, all the opinions expressed in this piece should be considered as my own personal take on the developing media landscape, and not necessarily those of my employers or the department in which I work.

Another quick song recommendation before I’m pulled off to bed. There’s this song by Nina Simone that I’ve been listening to a lot lately which you can get on the Anthology album. It’s called

Another quick song recommendation before I’m pulled off to bed. There’s this song by Nina Simone that I’ve been listening to a lot lately which you can get on the Anthology album. It’s called