I’ve got Matt Biddulph staying with me and been hanging out with Paul Hammond a lot recently again and since they’re both ex-BBC colleagues, we’ve inevitably found ourselves talking a bit about what’s going on at the organisation at the moment. And it’s a busy time for them – Ashley Highfield and Mark Thompson have made a couple of interesting announcements that contain a fair amount of value nicely leavened with some typical organisational lunacy and clumsiness. But that’s not what I want to talk about.

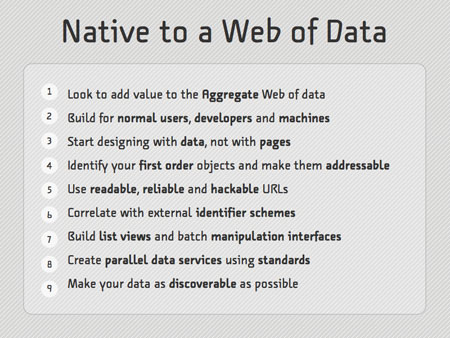

What I want to talk about is this, which is a link that I’ve already posted to my del.icio.us feed earlier in the day and will turn up later on this site as part of my daily link dump. For those who don’t want to click on the link, here’s the picture:

Now this is a photo taken in the public reception area of BBC Television Centre, but I want to make it really clear from the outset that you shouldn’t be taking it literally or seriously – it’s a prop, a think piece, to help people in the organisation start think about the issues that are confronting them and start to come to terms with it. It has, however, stuck in my head all day. And here’s why…

The apparent shock revelation of the statement – the reason it’s supposed to get people nervous – is because it intimates that one day a new distribution mechanism might replace broadcast media. And while you’re reeling because of that insane revelation and the incredible insight that it contains, let me supplement it with a nice dose of truism from Mark Thompson:

“There are two reasons why we need a new creative strategy. Audiences are changing. And technology is changing. In a way, everyone knows this of course. What’s surprising – shocking even – is the sheer pace of that change. In both cases it’s faster and more radical than anything we’ve seen before.”

So here’s the argument – that perhaps broadcast won’t last forever and that technology is changing faster than ever before. So fast, apparently, that it’s almost dazzlingly confusing for people.

I’m afraid I think this is certifiable bullshit. There’s nothing rapid about this transition at all. It’s been happening in the background for fifteen years. So let me rephrase it in ways that I understand. Shock revelation! A new set of technologies has started to displace older technologies and will continue to do so at a fairly slow rate over the next ten to thirty years!

I’m completely bored of this rhetoric of endless insane change at a ludicrous rate, and cannot actually believe that people are taking it seriously. We’ve had iPods and digital media players for what – five years now? We’ve had Tivo for a similar amount of time, computers that can play DVDs for longer, music and video held in digital form since the eighties, an internet that members of the public have been building and creating upon for almost fifteen years. TV only got colour forty odd years ago, but somehow we’re expected to think that it’s built up a tradition and way of operating that’s unable to deal with technological shifts that happen over decades!? This is too fast for TV!? That’s ridiculous! This isn’t traditional media versus a rebellious newcomer, this is a fairly reasonable and incremental technology change that anyone involved in it could have seen coming from miles away. And it’s not even like anyone expects television or radio to change enormously radically over the next couple of decades! I mean, we’re swtiching to digital broadcasting in the UK in a few years, which gives people a few more channels. Radio’s not going to be fully digital for decades. Broadcast is still going to be a dominant form of content distribution in ten and maybe twenty years time, it just won’t be the only one. And five years from now there will clearly be more bottom-up media, just as there are more weblogs now than five years ago, but I’d be surprised if it had really eradicated any major media outlets. These changes are happening, they’re definitely happening, but they’re happening at a reasonable, comprehendible pace. There are opportunities, of course, and you have to be fast to be the first mover, but you don’t die if you’re not the first mover – you only die if you don’t adapt.

My sense of these media organisations that use this argument of incredibly rapid technology change is that they’re screaming that they’re being pursued by a snail and yet they cannot get away! ‘The snail! The snail!’, they cry. ‘How can we possibly escape!?. The problem being that the snail’s been moving closer for the last twenty years one way or another and they just weren’t paying attention. Because if we’re honest, if you don’t want or need to be first and you don’t need to own the platform, it can’t be hard to see roughly where this environment is going. Media will be, must be, transportable in bits and delivered to TV screens and various other players. And there will be enormous archives available that need to be explorable and searchable. And people will create content online and distribute it between themselves and find new ways to express themselves. Changes in the mechanics of those distributions and explorations will happen all the time, but really the major shift is not such a surprise, surely? I mean, how can it be!? Most of it has been happening in an unevenly distributed way for years anyway. And it’s not like it’s enormously hard to see what you’ve got to do to prepare for this – find a way to digitise the content, get as much information as possible about the content, work out how to throw it around the world, look for business models and watch the bubble-up communities for ideas. That’s it. Come on, guys! There’s hard work to be done, but it’s not in observing the trends or trying to work out what to do, it’s in just getting on with the work of sorting out rights and data and digitisation and keeping in touch with ideas from the ground. This should be the minimum a media organisation should do, not some terrifying new world of fear!

I think this is the most important thing that these organisations need to recognise now – not that change is dramatic and scary and that they have to suddenly pull themselves together to confront a new threat, but that they’ve been simply ignoring the world around them for decades. We don’t need people standing up and panicking and shouting the bloody obvious. We need people to watch the industries that could have an impact upon them, take them seriously, don’t freak out and observe what’s moving in their direction and then just do the basic work to be ready for it. The only way that snails catch you up is if you’re too self-absorbed to see them coming.